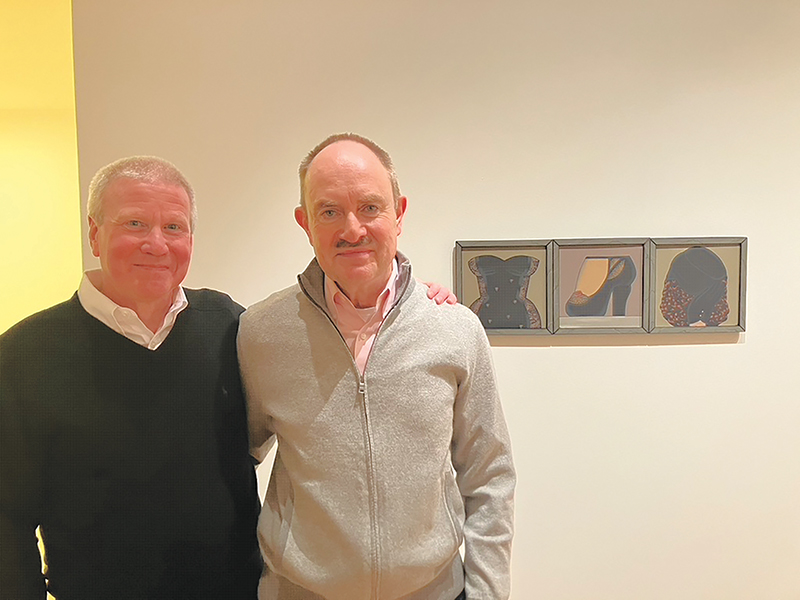

Collector Profile: Tom Guenther and Kerry Herlihy

By BIANCA BOVA

Inside a classic Chicago walk-up apartment on Logan Boulevard, characterized by warm woodwork, high ceilings, and wavy glass windows offset by thoughtfully selected Italian modernist furnishings, is where Tom Guenther and Kerry Grace Herllihy reside and where an art collection is as telling of its owners’ taste as it is of the city’s.

Guenther and Herlihy lived on the West and East Coasts respectively, before settling down together in Logan Square. Guenther is a Full time Preparator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, who has also worked in turns for the Art Institute of Chicago; under the auspices of Terry Dowd International; and for hire at art fairs around the country, in addition to holding posts at various galleries along the way. Herlihy on the other hand, works in tech in Enterprise Customer Solutions.

“We have the feeling Chicago is where we're going to stay, and investing in Chicago artists is really important to us,” notes Herlihy, “I've been fortunate. My grandma really turned me onto art when I was young. She was a representative for small artists in Tampa, Florida. My dad was a pilot, so I was able to travel a lot with my family, so collecting for me was about finding art from different places that just felt right at first. But now, I feel like we have more of a focus, and it is a local focus in many ways.”

“I worked as an art assistant when I was still living in Oakland, California,” says Guenther, “and I started collecting little knick-knacks from artists that have come and gone over the years, things by people I worked for or with. But when it came to collecting seriously, I kept thinking, ’Oakland? Am I really gonna be here for forever?’ So I stuck with collecting a lot of books and zines with artists’ signatures, and small, compact sort of works. Like Kerry said, now that we’re here, it feels like we can be a little more ambitious with it.”

Guenther then adds with a laugh, “Plus once we moved in together, it was kind of tight that we both had someone to go in on art 50/50 with!”

The collection unfolds thoughtfully, (if not densely) throughout the couple’s space. In an especially stunning instance, a Naomi Nakazato acrylic work is suspended from wires in a bespoke frame in front of the windows that look out onto the apartment’s sleeping porch. (“The benefits of living with an art handler!” quips Herlihy). Adjacent, alongside the Saporiti Missoni-upholstered couch, Mexican folk art figurines, and fragments of kiln-blown Theaster Gates pottery, hangs a mirror etched with Monikers and doodles, a playful homage to the couples’ artistic loves.

“There’s some Cy Twombly in there, all sorts of things. There are titles to Karl Wirsum paintings, and there are some Christina Ramberg drawings hidden too,” Guenther says, “It’s just a fun thing for us–a way to incorporate some of our favorites.”

A deep enthusiasm for Chicago’s Imagists is a dominant thread in the collection. In the foyer of the apartment hangs its crown jewel, an Errol Ortiz painting, The Runaway House (1983) the couple acquired from Who Modern in Skokie, Illinois. Part of a larger series of 12 works by the artist, it hangs companionably with two blind-object wire hands that project from the corner wall.

“The Imagists are really where it started for me,” says Guenther, ”About 12 years ago, I was living here in Chicago and working as a bike messenger. I was out in a rainstorm, and I was delivering a letter to a place between Superior and Ohio streets. There was a Zack Wirsum painting hanging in the front of Jean Albano Gallery. I saw it and decided to go in. Jean was there, and she was very welcoming. She started to tell me, ‘This guy's dad was really great. I got some of his paintings in the back that are from the '80s. They were sold in Japan, and I'm gonna show them in the US for the first time ever!’ So she brought me to the back and started showing me these Karl Wirsum paintings that hadn't been shown in the States yet. And I just thought that was so cool–the work of course, but also that she did that. Biking around, you see a lot of public art, and I started to notice all the Roger Brown pieces. There's one famous mosaic on LaSalle, the two Angel men, you know, right by the courthouse. NBC Tower had one, and the building next to the Chicago Architecture Center. It all made a real impression on me.”

At the entry of the apartment, the front door is flanked on one wall by a work on corrugated metal by graffiti artist Riggs (“It’s a strange one,” notes Guenther, “it has rope that has epoxy on the back–that’s what you hung it from. Of course the rope’s going to dissolve long before the epoxy does.”) and on another by a painting by Chicago artist Jonathan Worcester. The latter was acquired from a 2024 exhibition at Cleaner Gallery.

“I really hadn't seen Jonathan's work until we went to the University Club,” Herlihy says, “When I saw that show, I was blown away.”

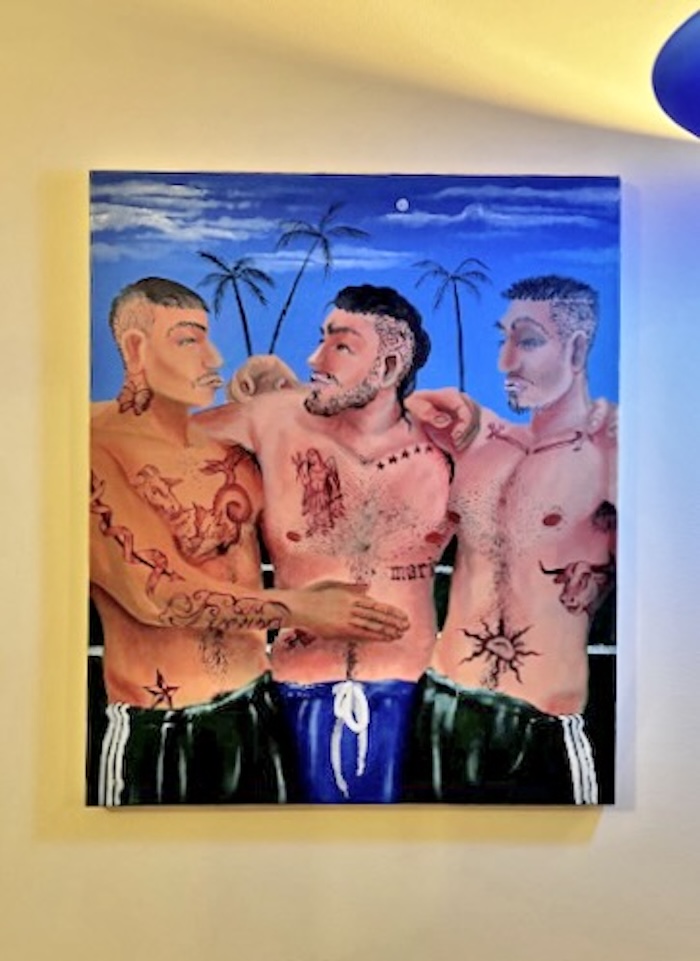

Jonathan Worcester

“We’re also big fans of Cleaner, of Ari Norris and Ryan Burns, the owners,” says Guenther, “so when we saw Jonathan’s show there, the next day I texted him about a painting. It’s heavy as hell, but man we got a good one. He’s such a good guy too, I knew him from working at the Art Institute.”

“That’s really our ideal situation,” continues Herlihy, “buying a work of art we really love in a way that supports Chicago artists and galleries, who are also just people who we really, genuinely like. We don’t think about market value too much or try to be speculators. I mean of course you want to see the artists you like succeed, but more importantly, you want to believe that something holds value just because we love it so much.”

Around the corner, the kitchen contains a cheeky mix of Juan Palacios paintings, H.C. Westermann photos, and work by Guenther (“I don’t really make much anymore,” he shrugs modestly, “mostly gifts for friends or family.”). Deeper into the apartment, one finds an increasingly eclectic mix–a 1980s ceramic wall piece acquired at auction that was once modified into a clock, Sean Gannon drawings, folk paintings on tin from the Mercado la Venia in Mexico City, a textile piece by Norman Laliberté passed down from Herlihy’s grandmother outfitted with custom cherrywood brackets built by Guenther. Alongside the neo-Imagist and folk aspects, an interest in outsider art is legible in the collection. One such piece that stands out is a framed work of mail art.

“It’s a work by Buzz Blur. He was the Moniker writer Colossus of Roads. We were selling his art at a gallery I worked at in 2015, in the West, called SubTerra that existed for like, six to eight years. He wrote this letter to me, and in it was an alias of his real name, and his brother's age–that’s circled. He handmade and would print these off these stamps, and they would actually go through the mail. It's crazy. He lived on a train line in Arkansas. He writes and also would speak in this kind of poetic, Victorian-esque way. He was so kind. The Massillon Museum in Ohio acquired most of the work from that show. I’m grateful for the letter as a memento,” says Guenther.

It is this attitude and approach that leads one to believe that though Guenther and Herlihy’s collection is young (as are they themselves), one can see clearly in their enthusiasm, sincerity, and respect for Chicago’s art historical legacies the wider footprint it is sure to eventually fill out.

#