Excerpt from Artist Tony Fitzpatrick's Upcoming 2025 Book

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

Last fall artist Tony Fitzpatrick shared he was working on another book. As he gets closer to publishing the book, he shared excerpts with CGN as well as what led him to create this latest project, a familiar concoction of poetry and art about Chicago as well as how an artist finds inspiration in the everyday.

"Back when I started drawing pictures in earnest, I couldn't afford paint," recalls Fitzpatrick, "But I had every kind of Prismacolor and graphite pencil known to man. I preferred drawing, something about that first mark's impact – it was immediate. I love drawing with brushes, pencils, etching needles, you name it. Anything that slakes that caveman's thirst for making a mark on something... I liked all manner of surfaces, from copper plates, slate Boards, really good art paper as well." He said the experience was simple, and transformative, "It was me and my Pencils."

Fitzpatrick rented a storefront for $75 a month in Villa Park. He recalls it had an unusual address: 125 1/2 S Villa. The 'half' he never understood, but he says he accepted it because he found out very young that you don't want to piss off the Post Office. In fact, he went out of his way to convey a sort of delivery friendship. "One of the things I did," he explains, "was make art on blank postcards and mail them to myself. I made sure I got mail everyday at that weird address." Thinking about those early days, Fitzpatrick says he intends to revive the postcard mailing again soon, except he will actually mail them out to people he knows and whose address he has.

Early on Fitzpatrick says he realized that having his own space to go and draw everyday was a thorough kind of freedom. "It was my 300 square feet of the American dream, and I could do whatever the fuck I wanted in it. It was a kind of gravity. I always had someplace to go. I could make the world I'd imagined there." The freedom didn't mean perfect days. The artist had by then gotten into a fair share of trouble. He says plenty of people he knew were skeptical of him, even considering him a weirdo and an outcast. He was barred from most of the bars and establishments he'd been thrown out of for fighting. No longer drinking, Fitzpatrick says he set about drawing.

"I drew what I remembered, what I loved. I drew Birds, naked Women, characters from cartoons and Sunday comics. I drew a lot of Boxers, both famous and unknown. I drew petty criminals I knew, sad stories, many images from Coney Island from a visit to New York. I drew whatever was in my heart–the world I would come to inhabit."

CGN will share an update when Fitzpatrick's book is published.

Follow Tony Fitzpatrick on Instagram for art and updates

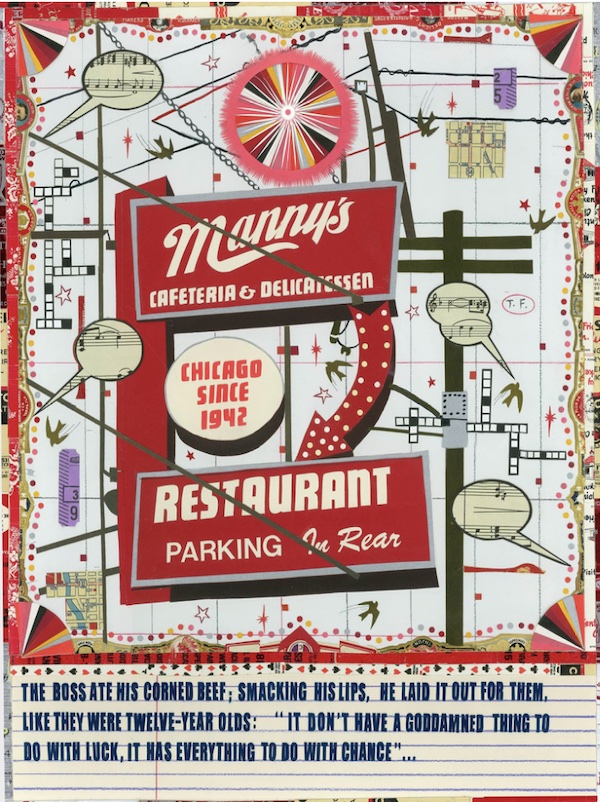

A STORY OF A CHICAGO PLACE...MANNY’S

You go through the cafeteria line at Manny’s and you marvel:

Brisket. Corned beef and pastrami sandwiches as big as your

head—and as garlicky as a Greek waiter. A heart attack on a

plate, accompanied by a huge, salty, dill pickle and a potato

latke. You yuck it up with the sandwich guy and he enhances

your pile of meat even more.

You can eat here. Meaty stuff. The kind of meal you want before

they execute you. The kind of sandwich you eat with a friend,

then take the other half home for dinner, and breakfast the

next day...and maybe lunch as well.

Look around. There are City Hall creatures, cops, aldermen,

Streets and San guys with yellow neon vests and meter maids

shoveling down slices of pie. There are deals being cut. Bonds

being haggled over. Ticket quotas pondered and the grimy

business of the sidewalk being brokered. The preferred music?

The ringing of the cash register.

The preferred currency: green cash money.

They frown a little when you hand them the debit card with the

chip in it; it’s another pain-in-the-ass-thing the new century

has grafted onto everyone. You also get the shit-eye if you are

one of those who babbles on your cell phone in the middle of

the cafeteria line, even at your table. People are trying to eat,

Numb-Nuts. Nobody wants to hear your bullshit here. Take it

outside, Schmuck-O, because here, people are eating or

working—like it’s always been, since Moses.

I see a guy slide an envelope across the table with a wry smile.

“Christmas card,” he says. The guy across from him wordlessly

puts it in the kangaroo pocket of his hoodie without so much as

looking up or saying thank you.

There is a lady walking an Irish Wolfhound in front of the

window. The dog is excited; he can smell the meaty goodness. I

also notice he is wearing dog boots, and not happily. A guy

comments, “Jesus Christ, she put shoes on the dog. Look! He's

trying to kick ‘em off! He don’ want to look like a jag-off in front ‘a

the other dogs.” They meander by, the hound alternately fighting

with his goofy boots and sniffing at the meaty air he is

enshrouded in.

He looks confused.

There is a valet there—a big burly guy in a neon yellow vest,

quietly watching the street and reading the traffic for the slow-

roll of an incoming parking task. They’ve remodeled the joint, but

it hasn’t taken away any of the atmosphere in the least—and this

place has atmosphere in spades.

If someone asked me to take them to ONE place which defines

this city, I might take them here. Or to night court at 26th and

California. Or Ricobene’s for a breaded steak sang’wich. Or Army

and Lou’s, except...it’s gone now; and maybe the bounty of great

Mexican joints in Pilsen. I’d also include the Maxwell Street

Polish and hotdog joints—the one built in the middle of a used

car lot at 56th and Western is among my favorites.

These places are adorned in the colors of urgency, of exigence:

rich reds, yellows and sequential blinking lights. As a kid I

thought these places were what a heaven was supposed to look

like: a carnival of lights and color and food smells. There was this

promise here, that you would never be hungry, and the world

was not merely a well-lit nowhere, but a wondrous place full of

lights and magic and hope. It was a mystery that you solved

every time it got dark and those lights were on.

I can’t eat Manny’s fine sandwiches anymore; my cardiologists

would blow a gasket. But I can watch as other people enjoy them.

About the only thing I can eat there anymore is the Jell-O and the

coleslaw, and who the fuck wants to eat that?

For me, the best thing to eat there was the pastrami. Damn, it is

good—greasy, salty, garlicky and piled high on rye with a big

slice of dill pickle and a latke. This might be the best thing I have

ever eaten. I never could get through a whole sandwich, but my

dog Chooch was very happy to share the second half with me a

day later. We were smelling very special after a Manny’s binge—I

always blamed the dog.

It is one of those places where one is happy for the lack of

change. Sure, they remodeled it, but damn if they didn’t preserve

the character of the place—inhabited by and for working people.

There are no conversations about beer programs, or sommeliers.

This is belly to belly, elbow to elbow—a joint that caters to the

elementally hungry. The kind of hungry you get if you operate a

jackhammer or a cement mixer; or hoist dumpsters for Streets

and San. There is nothing delicate here. Even the City Hall guys

are the worker bees—the ones who actually DO the work their

bosses take credit for on the news. It is one of those eateries that

grinds out the goods and tastes like the city we claim to be, hearty and good.

One of the best things to do here is to just overhear stuff—not

eavesdrop—but overhear the great thoughts of people on break

from work...airing out things they don’t say around their bosses.

Things like this:

“You can’t get it with too much peppers—you don’t want the

sang’wich you’re eatin’...to be eatin’ YOU.”

“If I had a face like his...I’d paint my ass and walk on my hands.”

“Oh yeah, he’s got a face for radio.”

I love hearing the curbside philosophies and stories, the hard-

earned bits of knowledge that come from punching a clock and

grinding it out forty hours at a time and wondering what the hell

it is all for—the American horse sense of the people who built

this city. This is the school nobody ever tells you about: the

native intelligence that comes from being a citizen, the act of faith

that working people carry out every day that keeps this city

lurching along.

One time when I was there, years ago, I heard this gem: “My

boss laid it out for me like I was a fuckin’ twelve-year-old. He

says, ‘It don’t have a goddamn thing to do with luck, pal...it’s

got everything to do with chance.'”

Which, for some reason, makes more sense to me every day that I live.

*

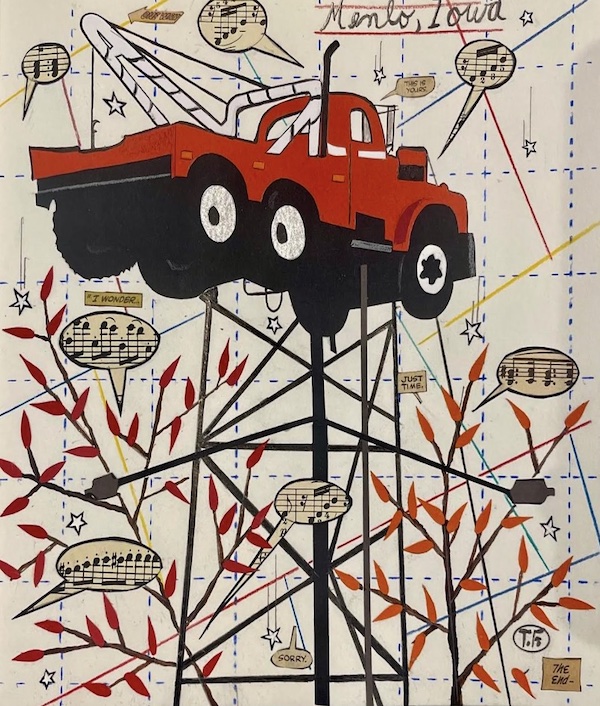

MOTOR GYPSY (Menlo, Iowa) for Charlie

* This piece and poem was written about a friend I went

through rehab with in 1983. He was the first person I ever

knew who died of AIDS. In fact, he died of it before they were

even calling it AIDS...

Charlie did an immense amount of good before passing away.

He guided a great many people into recovery and was a font

of hard-earned wisdom about addiction. I saw this old-time

rig suspended 25 feet above the ground in Menlo, Iowa and

immediately thought of Charlie: a long-haul trucker who'd

always wanted this kind of old-timey Mack truck with the

bulldog hood ornament.

In my book? The man was a Saint...

__

Truck.

Charlie hauled peaches from Georgia to San Diego,

Pears and apples from Yakima, Washington to

Lincoln, Nebraska and Rock Island, Illinois.

Perishables.

On a clock.

28 Hours.

46 hours.

Black crank sprinkled into

the endless river of Thermos black coffee.

Hands shaking off the nods.

He played Charlie Rich

and George Jones songs on his 8-track.

Under the pitch black Montana skies,

his eyes blurred and he saw

comet grease and meteor showers.

Under an arc of star lights,

he pulled over and slept.

He'd seen it all, man –

hunger, thirst, rest

and half the angels

in a skittering dervish on

the 3,365 miles between

Oregon and Boston;

every mile marker and weigh station from A1A to Pacific 1.

He tried not to think about

the truck stop blowjobs.

The ones he got,

the ones he gave,

and wondered if he'd ever stop shaking

or recognize the phantom in the mirror ever again.

He ground his teeth to nubs.

His clothes barely fit

and were damn near falling off.

The older over-the-road guys would say to him,

in a hush, "This is where you disappear brother.

This is how.”

Charlie found himself driving south on Pacific 1

toward Escondido and he noticed the ocean.

He was startled to realize he'd never stepped into it.

Never felt the warmth of the Pacific on his skin.

He pulled the 18-wheeler over.

He left his boots in the rig.

He walked through the warm sand

weeping a child's tears,

right into the surf

and the linen-like motion of the tide,

and for the first time in his life,

he sang.

Motor Gypsy.

Fly.

*