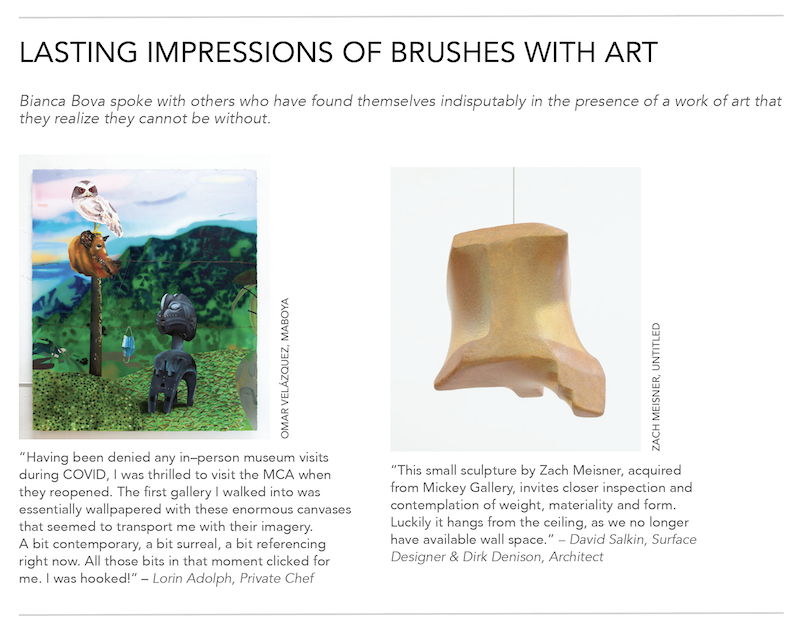

Notes on Collecting: A Young Collector Shares Her Serendipitous Acquisitions

By BIANCA BOVA

The art you love and the art you wish to live with—the art you are capable of living with—are not promised to be the same. I learned this working as a gallery officer at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago about a decade ago. I was posted in Warhol and Marisol, an exhibition examining foundational works in the museum’s permanent collection by the two luminary artists. The small space was filled with sculptures and paintings that continually rewarded the sort of slow, deliberate looking that long days working on the museum floor allowed for, and I was genuinely happy with the assignment. One work by Marisol in particular, Andy, a portrait of Warhol that included a worn-out pair of his shoes, delighted me above all else. The bodily immediacy of the leather, retaining a broken-in contour of the artist’s feet lent, for me, a sense of sacredness to the space.

One evening, working an overnight shift, I was surprised to find myself hesitating to enter the exhibition, suddenly overcome by uneasiness. Its locus was another Marisol sculpture, Self-Portrait. Self-Portrait features seven heads, some bearing partially-cast faces, and a disproportionate number of limbs and breasts distributed across a long, shared block of a body. It also contains an element that may be interpreted as a sort of profane counterpoint to the sanctity I saw in Andy’s shoes. The sculpture’s materials list has the startling inclusion of “human teeth,” which are indeed visible in at least one of the heads’ open mouths. A member of the preparatory staff had shared with me an (unconfirmed) piece of trivia, that Marisol had, unaided by a dental professional, extruded some of her own teeth for incorporation in the work. Alone in the dark with the sculpture, my only thought was: How could this have come from a private collection? Who has the equanimity to encounter pulled teeth in art on the way to the bathroom, in the middle of the night?

Until that late night encounter with Self-Portrait, I had never given the motivations of art collecting any serious thought; but from then on, it has remained for me a point of obsession. When you look past mere personal taste, there is a spectrum of collecting practices, ranging from the rigid policy of “40 artists and 100 works” famously adhered to by mega-collectors Stefan Edlis and Gael Neeson, to the more freewheeling approach I got to know during my years in the orbit of Lawrence & Clark, the beloved Chicago collection gallery. Add to these the oft-cited 30/30/30 rule: that when building a collection, one should hedge their bets and aim for 30% of the art to rise in value, 30% to retain a stable value, and accept that 30% may lose value. Regardless of the theories and formulas and forecasts collectors may rigidly adhere to, one prevailing principle seems universally true: you don’t choose the art, the art chooses you.

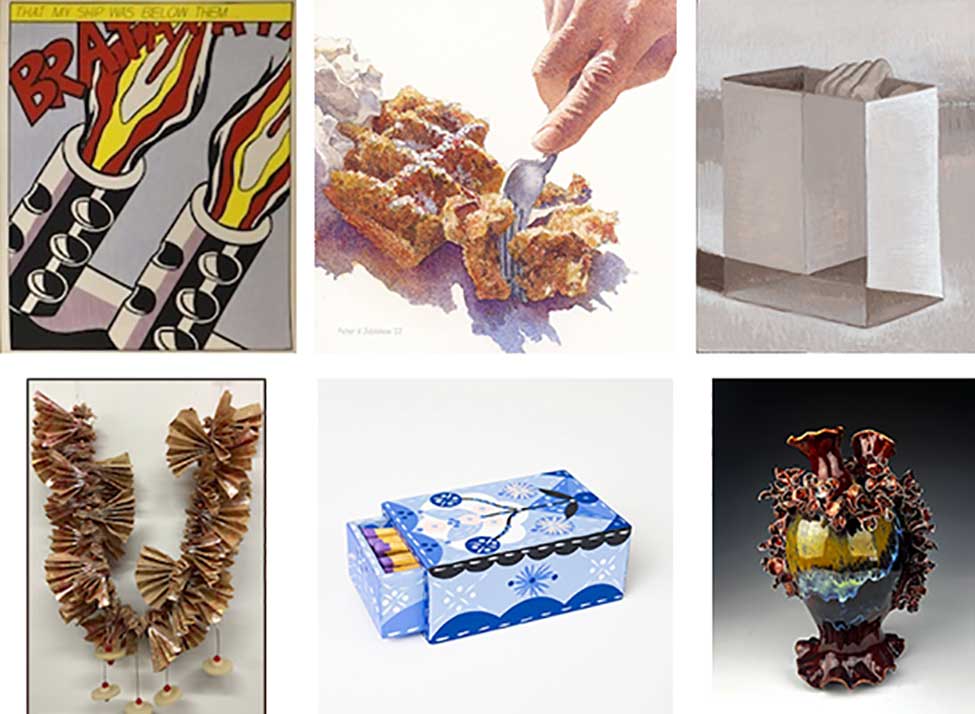

Despite or in spite–I don’t know which–of my preoccupation with collecting, I decided from the start that I would not buy art myself. In what I’ve come to think of as a kind of payoff for not having any life outside of the art world, as well as a testament to the astonishing generosity of artists, I have somehow still managed to build a modest collection. Two paintings, by Sarah Leuchtner and Michelle Grabner, hang on the wall above my bed, mirroring the pillows below and their suggestions of bodies, while an early typographic work in stainless steel by Jacqueline Surdell occupies the floor between the windows and the radiator. In the dining room, which doubles as my home office, a large-scale photograph by Alan Cohen depicting the Illinois–Wisconsin border occupies the most prominent wall. Prophetically, the work was obtained on a long-term loan from a friend’s private collection shortly after I moved into my current apartment, and well before my curatorial practice came to include working remotely to produce several large exhibitions in Milwaukee. Also in the dining room hangs a collage by Jason Pickleman. Bestowed upon me as a gift on my 30th birthday, it is work that I had openly coveted for years, since my first visit to his studio, and which I can hardly believe I now have the privilege of living with. Flanking one side of the front door are two found lawn signs advertising bankruptcy liquidation services, hung as a diptych; visually compelling in their own right, they also serve as a daily tongue-in-cheek reminder of my own professional relationship to the affairs of auctions. On the other side hangs an anonymous black and white photograph of a woman bathing while her laundry dries above her, a era–less image that feels totemic of my twenties. On my bookcase among the exhibition catalogs is a small print by Matthias Neumann, an artist I have admired and worked with since I was a teenager, and a minimalist ceramic ghost by Polly Yates that was thoughtfully delivered to me in the thick of the pandemic, “for company,” under the pretense that you’re not alone if you have a ghost in your house.

Notably, none of the above works were acquired from a gallery–most came straight from the artists’ studios. Many are from exhibitions jointly mounted, particularly memorable studio visits, or gifts on occasions of personal significance. And for a long time, I was certain that art collecting would remain for me an incidental practice.

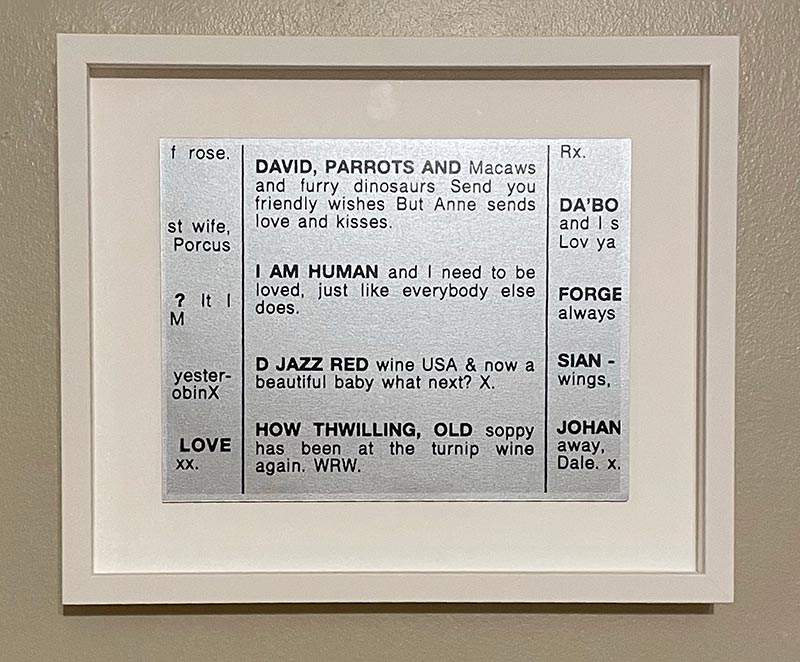

That changed on the last day of this year’s edition of EXPO CHICAGO. I was in an upstairs office chatting with an acquaintance about her and her wife’s art collection, when the conversation turned to a work on the show floor by an artist we both admired. I admitted that, uncharacteristically, I had been considering acquiring the work for several months, by which I meant I’d been torturing myself about spending a relatively modest sum of money on something that I wanted, but could not convince myself there was any reason I should own. At her urging–and with about 25 minutes left before the fair closed–I walked down to the booth to view it again. While I was deliberating its merits, another work in the booth caught my eye. It was a small Xerox copied monochrome on silver paper, an editioned print by the British artist Jeremy Deller.

The print features an enlargement of an excerpt from the classified ad section published in The Guardian on Valentine’s Day 1996. Entitled 14/2/96, the ad itself was originally commissioned from the artist by curator Matthew Higgs, as part of Imprint 93, Higgs’ experimental mail art-focused publishing venture that was active in the mid-1990s. The print was produced under the auspices of Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, and released by Printed Matter on the occasion of an archival exhibition focused on Imprint 93, which Printed Matter produced in partnership with Whitechapel Gallery in 2018. At the time, I knew none of this. All I knew was that I vaguely recalled Jeremy Deller was a recipient of the Turner Prize at some point, that the print cost more than the work I had come downstairs to look at, and that I absolutely had to have it. It now hangs above my nightstand.

“Once you start buying art, you’ll never be able to stop,” is something I have been told, verbatim, by every serious art collector I know. A member of the newly converted, I believe them. The exhilaration of acquisition unfolds across time from the heat of the moment when you recognize that a work belongs in your collection, through the anxiety of availability, the gravity of transaction, and finally the perpetual satisfaction of seeing the work on your wall day after day. The greatest collectors are those who allow themselves to be guided by these forces, and the greatest collections those which are allowed to flourish as a record of a life well-lived in the art world.