The Gallery Continuum: Reviewing Spaces Standing the Test of Time

By BIANCA BOVA

Chicago’s place in the commercial art world has always eluded easy categorization. You can find as many people who insist its relevance is ironclad as you will those who insist it is little more than an afterthought in flyover country. As time and the tides of the market have shifted, both have been true in turn. While Chicago’s galleries may not operate competitively with, say, New York in terms of real estate (Gagosian’s Chelsea location alone occupies 25,000 square feet), or with London in terms of historical pedigree (Colnaghi, Est. 1760) its defining merit is its galleries’ highly individualized programs.

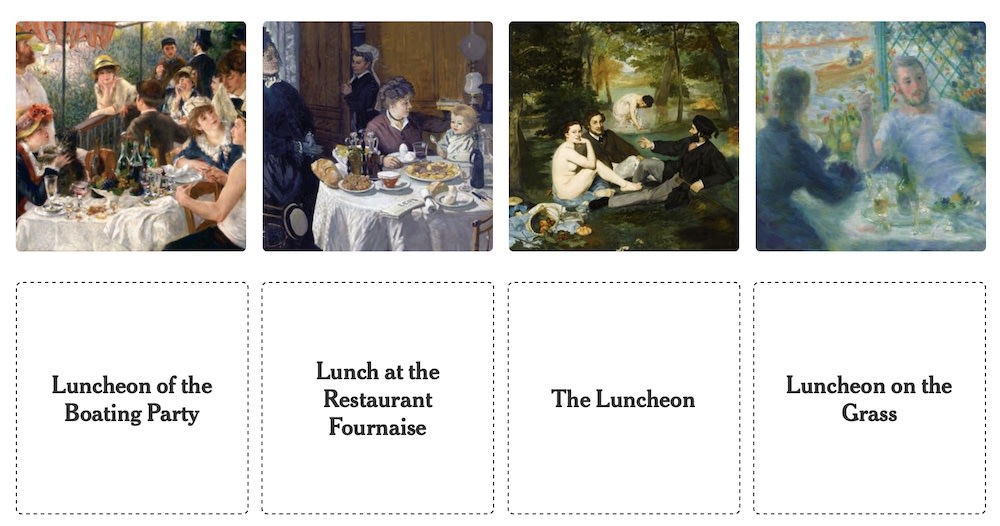

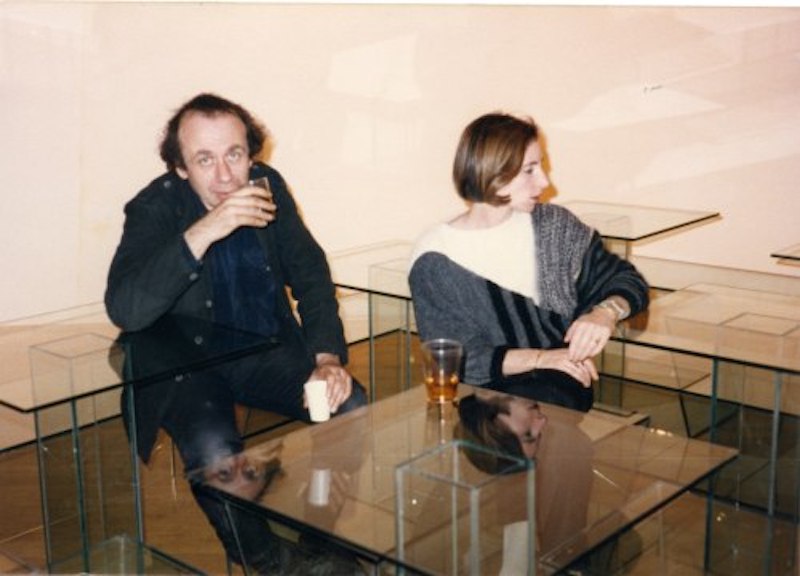

There are the galleries which have for decades served as tent poles for the Chicago art world–beginning with Rhona Hoffman, its doyenne. The gallery’s artist roster reads like the table of contents of a twentieth century art history book: Sol LeWitt, Gordon Parks, Jenny Holzer, Gordon Matta-Clark, Vito Acconci. There is also a prominent Chicago streak: Michael Rakowitz, Amanda Williams, Judy Ledgerwood, Richard Rezac, Julia Fish. Few are the galleries (and fewer are the dealers themselves) who endure long enough to restage significant works, as Hoffman did in exhibiting Acconci’s Maze Table, first in 1985-86, and then again in late 2022. This dual model of developing the careers of the brightest artists working, while also maintaining a commitment to their practices long enough to introduce their canonized works to a second generation is, quite simply, art dealing in service to its highest purpose. It’s also not a bad way to make a living.

Richard Gray is another name that looms large in Chicago’s commercial history. The gallery’s recently mounted anniversary exhibition, GRAY at 60, included works by sixty artists who have shown with the gallery (or whose works the gallery has specialized in) since opening its doors on East Ontario in 1963. Representing over a century of art making, the exhibition rivaled a museum show in its scale and scope.

Despite this grandiosity, GRAY’s program is so well-defined as to leave a kind of signature on art collections it has helped to build.

In a recent New York Times profile on winemaker Maggie Harrison, it was noted that Harrison, now in her fifties:

“Grew up in a suburb of Chicago,” and that her parents’ “passion was collecting art. The walls of their otherwise unremarkable house were crowded with canvases by David Hockney, Alex Katz and Chuck Close. A large painting of a heart by the artist Jim Dine hung in Harrison’s bedroom.”

Is there any question what gallery her parents were clients of?

Reaching such milestones as Rhona Hoffman and Richard Gray have first requires surpassing other, smaller milestones. MICKEY, as well-appointed a gallery space as you will find anywhere (unsurprising given that it is the work of Dirk Denison Architects), has just reached one, celebrating five years of operations on Grand Avenue last month. As evidenced by MICKEY, a summer group exhibition, a survey on view until September 10th that includes a work by every artist the gallery has shown since opening its doors, the program there is, in a word, wild. It seems distinctly possible that the only straight line that can be drawn through the work of Michelle Grabner, Michael Madrigali, Paul Heyer, Leonardo Kaplan, Chloe Seibert, and Zach Meisner is gallery owner Mickey Pomfrey’s almost alarmingly keen eye. Pomfrey is, after all, one of the first dealers to have shown the work of art star Puppies Puppies (Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo), albeit under the auspices of an earlier space, Courtney Blades. The highly refined strangeness of MICKEY’s program is perhaps only rivaled by the highly refined strangeness of the gallery’s informal, in-house wine program. Ask director Tim Mann to recommend a bottle before your next dinner party; you won’t regret it.

This hyper personalized approach to programming a gallery is not a new concept. A look over the exhibition history at Dan Devening’s gallery, Devening Projects (one of the first spaces to make the move to Carroll Street in West Town) shows a veritable who’s-who of the last two decades in the Chicago art world. While it’s no surprise to see names like Nathaniel Robinson, Richard Rezac, Jin Lee, Peter Fagundo, and Christine Tarkowski on the roster, it’s often a curiosity to see when in their careers Devening mounted these shows. What’s more fun is to see the names of dealers, curators, and other industry figures who maintain their own practices as artists crop up, including Jason Pickleman, Aron Gent, and Sterling Lawrence. Add to this Devening’s impressive CV as an artist himself, and his long tenure as a member of the faculty of the School of the Art Institute, and you’d be hard-pressed to find someone more professionally embedded. Bearing this all in mind, it would serve collectors attracted to young talent well to keep an eye on the emerging artists like Zander Raymond, Maggie Crowley, and Jacqueline Surdell that show with Devening.

These are, of course, homegrown examples of why Chicago’s market has sustained. Long is the list of great galleries that had their genesis in Chicago and later expanded–Feature, Richard Feigan, GRAY, and Document, to name a few–and rightfully so. In more recent years, Chicago has also become an attractor of galleries established in other markets. Mariane Ibrahim Gallery moved operations in 2019, closing its original headquarters in Seattle in favor of relocating to Chicago. Having subsequently expanded to Paris in 2021 and Mexico City in 2022, bypassing the opening of any additional domestic spaces, it seems Chicago serves the gallery’s American market more than sufficiently.

With the recent acquisition of EXPO Chicago by Frieze, and the rampant speculation surrounding the likelihood of a significant uptick in the blue chip art market in the city it might bring, one wonders if Chicago will increase in desirability as location for future outposts of other galleries with established global footprints. Perrotin? LGDR? Gagosian? A girl can dream.

While there is much to be said about the economics (macro and micro) of the art market, and the geographic and political boundaries that have a way of regulating it (or not), at the end of the day, there is no greater force or factor that defines a gallery than the vision of its founder, and the program they build. Chicago is rich in these legacies. Taking into account the view from this moment, it appears it will be for generations to come.