#INSTAArt: Instagram's Independent Art Connections

By SARAH ADLER

Lee Godie sold her work on the steps of the Art Institute.

A self–taught artist, she insisted her work was better than Cezanne’s. But, it was the late ‘60s, decades before the advent of the Internet, and nearly half a century before Instagram would commandeer the public conscience. In terms of self-promotion, well, the steps of the Art Institute would have to do.

Although the internet has revolutionized everything – how we connect with one another, how we look at art, even how we create art, a simple fact remains the same: artists who are starting out, and those without traditional gallery representation, must be their own best advocate. Independent artists are tasked with a critical step after making their work: how to effectively share their art with a wide and engaged audience. Self–promotion can now be created and distributed, for the most part, digitially, originating entirely from the privacy of home or the studio, rather than out on the steps of a major institution. And many of the digital channels available are also, in large part, free.

I spoke with two artists without gallery representation on how they self-promote, and in particular, how they use the omnipresent social media application Instagram to do so. I also looked at greater trends in how artists feel about the controversial platform: does its universality and the algorithm of instant gratification ultimately undermine the art, even while bolstering the reach of one’s portfolio? I also wondered, what happens to galleries in the midst of all these great changes?

•

Haley Scott is a Chicago-based photographer who, on Instagram, goes by the sweetly enticing handle, @sugarmilkk. With more than 6,700 followers, a bio that proudly claims, “DETROIT MADE * CHICAGO BASED,” punctuated by the link to her professional website, Scott’s feed is a melange of photos united by rich hues as well as a sense of something intimate: there are close-up action shots of limber basketball players contorted into yoga-like positions, friends posing in moody lighting, and selfies of the artist herself modeling her own heavily tattooed arms. In many ways, Scott’s Instagram serves as both an ode to her work as well a window into her own identity.

“I know for a fact that whatever my brain is twisted up in makes me see colors differently,” she says, speaking of both her work as well as her personal Instagram. Last summer, a swath of luscious pinks and purples dominated her images; by December she favored rich blues and darker tones.

This kind of casual, light relationship to Instagram seems to be the exception amongst many artists today, at least according to several popular articles. A 2016 piece in Vice by the artist Brad Phillips claimed nearly the exact opposite with its doomsday title, “How Instagram is changing the art world” and subheader, “The app has made me more successful than ever, but at the expense of my own art.”

Written in the tone of an artist who is self-consciously biting the hand that has (literally) fed him luxurious six-course meals, Phillips acknowledges the ways in which his own presence on Instagram has dramatically boosted his art practice. Amongst his professional entrees, solo gallery shows and a book deal. His long list of drawbacks, however, underscores a kind of insidious aspect of the social media platform: that it sets up a system of instant gratification, it deletes any merit of privacy or creating work for oneself, and it can arbitrarily choose content to censor (if it transgresses vague community guidelines). In many ways, his criticisms aren’t too different from that of a regular (read: non-artist) user of the application.

“The app has been both an amazing and horrible tool for me, as well as other artists,” Phillips proclaims.

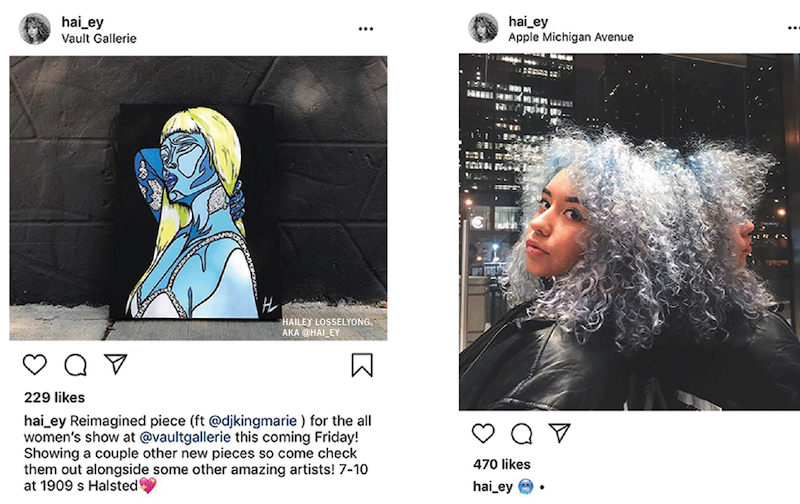

His frustration at the outwardly capricious nature of Instagram’s algorithms is mirrored by Hailey Losselyong, another Chicago-based artist who goes under the handle @hai_ey. Referencing the coveted ability to post active links in one’s Instagram ‘Story’ – a feature that, oddly, is only available to some, seemingly due to a high number of followers or some other account verification (another process with secret guidelines) – Losselyong says, “I think it’s strange that not everyone has access to all the app’s features.”

Despite her grievances with Instagram’s selectiveness, Losselyong warns that it is easy to hate on Instagram, when, in fact, it is also an incredible marketing tool, especially for artists who aren’t represented by galleries, or who do not employ or have access to a public relations team. Instagram, which is projected to surpass 111 million users in 2019, can serve as a very effective form of advertising. “It’s kind of a place to do a less refined version of a portfolio,” she says.

Like Scott, Losselyong does not shy away from the selfie. Her intricate, stylized drawings, characterized by fluid and looping lines, are followed up by equally glamorous images of the artist posing, making her feed a kind of ode to not just the art but the life of an artist: subversive, creative, edgy. In one image she sports a head of bleached white-blue and purple hair, using only a blue emoji as the caption. It isn’t a historically typical artist’s portfolio.

The effect of Instagram on art spreads beyond the individual artist. When it comes to galleries, Instagram has also introduced radical change. A 2018 Artnet.com article by Julia Halperin and Tim Schneider describes the phenomenon as an “Instagram takeover.” Gallerists acknowledge that they have discovered artists and evaluated images of art by using the app. Some also claim collectors pay more attention to a gallery’s Instagram posts than their email blasts (which, it’s worth noting, mostly replaced mailed announcements). Halperin and Schneider write, “By providing an unmediated, simple, and ever-present line of communication with collectors, Instagram has allowed the gallery to propel conversations begun with collectors at fairs into finalized sales back at the gallery at a later date…”

Like other social media tools, Instagram offers for galleries – which, are in simple terms, small businesses – access to free marketing and publicity. While algorithms may interfere with this in ways that wouldn’t happen in a magazine, per se, much can be said about the fact that not only is the content free, but it’s accessible to everyone. Instagram can ideally be a space to expose contemporary art to anyone who wants to engage with it, regardless of their ability to visit museums or frequent galleries.

Instagram, therefore, remains in a kind of polarized space. In many ways, the continual pressure the platform fosters – to create work and then promote perfect images of it – both helps and hurts artists. This modern means of sharing, beyond the steps of a museum, can also create great anxiety while pursuing independence, encouraging a singular quest for likes. According to Scott though, sharing her art on social media doesn’t change the fact that she has never done her work for anyone else. “It’s just the Aquarius rebel in me.”

@ChiGalleryNews follows many artists and galleries. Below are a few that have notable followings and frequently high post likes.