Kavi Gupta: Taking Chicago Artists Global

By KEVIN NANCE

In the community of art dealers in Chicago, Kavi Gupta stands out as one of the busiest and most ambitious. From his base in his eponymous gallery at 835 W. Washington, Gupta surveys an expanding mini-empire of exhibition spaces that now includes a branch in Berlin as well as two satellite spaces in Chicago (219 N. Elizabeth in the West Loop and 2108 S. California in Pilsen); in September, he plans to open a fourth Chicago space, a store specializing in art books and small editions, next door to the main gallery.

Over the years, Gupta has represented a core group of midcareer artists from Chicago—including Theaster Gates, Curtis Mann, Angel Otero, Melanie Schiff and Tony Tasset—but casts a wide net in terms of marketing them around the globe. More recently, his stable of artists has diversified in terms of geography, but Gupta’s approach to selling their work has remained consistently international.

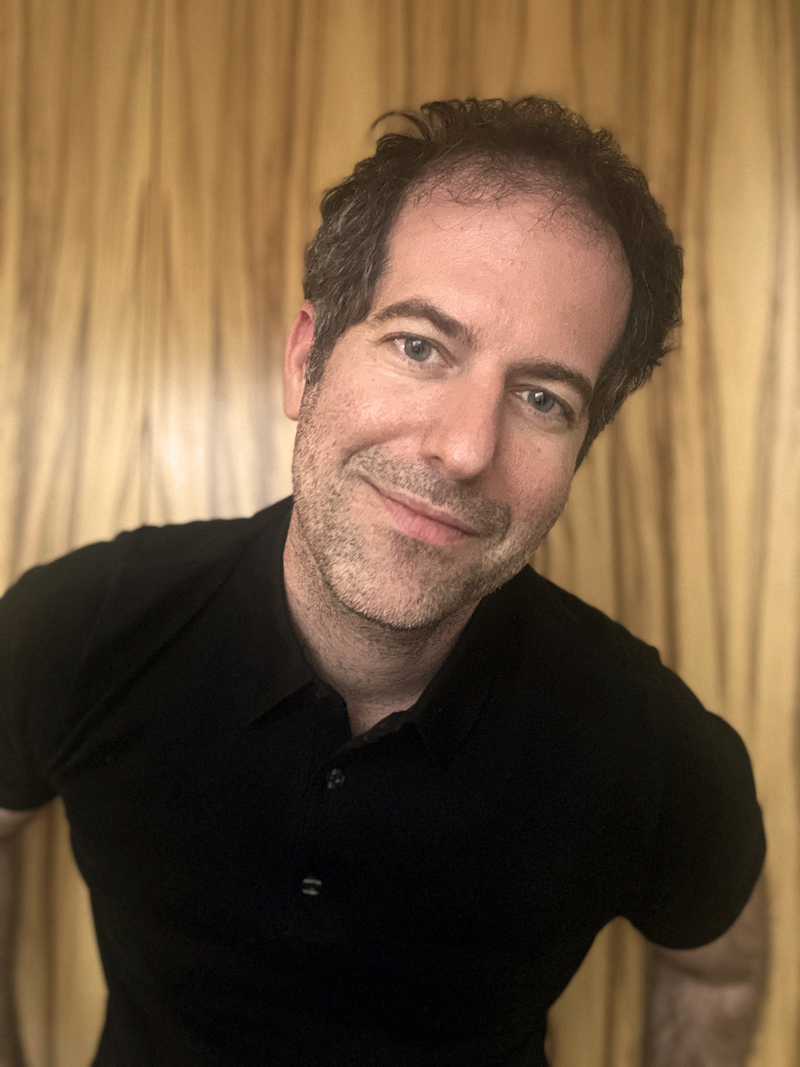

Chicago Gallery News recently visited Gupta, 45, at the Washington Boulevard gallery, where he also lives in a rooftop apartment with his wife, Jessica Moss, associate curator of contemporary art at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago. Following is an edited transcript of our chat.

What drew you to become an art dealer, and what was your preparation for it?

I started out collecting art. My family in India are some of the biggest collectors of contemporary Indian art. My father, Raj Gupta, was an architect and an engineer, who moved here in 1964 and worked with Bertrand Goldberg on Marina City. I was born in 1969, and our life was about architecture and design. I was an art history minor at Northern Illinois University; I was an investment banker after college but was spending all of my money on art. I went to get a master’s at the business school at the University of Chicago, and they allowed us to work with other departments. I chose the art history department, and that really propelled me into thinking I wanted to do something with art. I wanted to be around art, I wanted to be around artists, and I wanted to show what I was collecting. In the late ’90s, I found a building in the West Loop, a boarded-up crack house on Peoria, for a dollar a square foot. I called right there and said, “I’ll take it.” I built that space over two years, and I later bought the building across the street. As the West Loop developed, the value of those spaces went up, and we were able to leverage that into buying this building.

Fifteen years later, you’ve got a ton going on.

Yes, although the busyness, for us, isn’t really defined by how many people are walking through the door. We’ve positioned ourselves as a gallery that’s based in Chicago, but we don’t quantify our success based on things happening here. I just had a meeting with the staff, and they’re so busy that they can’t fathom how they’re going to get everything done. But it’s to do with all the things we’re doing around the world—collectors from everywhere, artists from everywhere. We’re a global gallery that just happens to be located here.

The majority of our artists are Chicago artists, but we’re promoting them around the world.

It’s not about foot traffic.

Right. In New York, it’s about dealing with who walks into the gallery; that’s their day. Our day is meetings and conference calls and research for artists and flying everywhere. Somebody from the gallery’s on the road all the time. We’re very proactive on behalf of artists, and that means not sitting here waiting for that client to come into our door. So our guys are out there talking to collectors, talking to curators, talking to art writers, pitching ideas and getting in front of them. If you look out my office door, you’d see two people packaging catalogs and other people writing proposals for museum shows. We have one person doing nothing but PR for specific artists. We have two people, who are artist liaisons, going to artists’ studios, talking about their practice, and talking about what’s coming next. It’s a constant back-office function and a high level of activity with a global focus.

What was the thought process behind opening the Berlin gallery?

It was part of this same thing we’ve been talking about. Berlin is a cultural capital, a place where curators and artists live and spend time. It’s about thinking; it’s about looking. And it’s a place where new art always comes from. For me Berlin has always been that place in Europe. It’s also very affordable, so it was a great place to make a European foothold. We wanted to reach out beyond Chicago and establish a beachhead for our Chicago artists, to have a different audience come and see the work, increase its recognition. It’s been very successful. We also use Berlin as a way to find new artists from Germany and elsewhere. Because it’s so affordable, artists come from all over the world and have studios there. There are artists from every city in Europe, as well as from Japan, China, and India. So it’s important for us to be there and see what’s really happening in contemporary art today.

You also have multiple spaces in Chicago. You just opened a new one on Elizabeth Street, for example.

That’s right, and we have a third space as well, an 11,000-square-foot building in Pilsen. The idea, basically, is to build opportunities for our artists. A lot of them work in large scale, and I wanted to give them the impetus to do that if they wanted to. We did a large show of Roxy Paine pieces, Apparatus, in the Elizabeth Street space that won the AICA [International Association of Art Critics-USA] Award as the best gallery show in the country; it took up two rooms and 5,000 square feet. It was a museum-caliber show, one of the bigger productions a gallery has ever done in Chicago. We also produced a Tony Tasset piece for the Whitney Biennial that was 80 feet long.

So you have three spaces in Chicago - you’re opening a fourth - and you have one in Berlin. That’s a lot.

It happened by need; it wasn’t really a conscious decision. Our gallery here isn’t that big, and we don’t have storage. At one point I was renting a storage building for $8,000 a month, and one of our collectors, a banker, said, “That’s ridiculous. Why don’t you go buy a warehouse, and your mortgage will be half of that for a bigger space.” So we bought the Elizabeth Street building, an 8,000-square-foot cold-storage facility that we renovated, and yes, the mortgage is less than half. And the space turned out so beautifully that we decided to start doing exhibitions there. And then the Pilsen space, a former auto garage, turned into the storage building.

So it’s not about establishing an empire.

Oh my gosh, no. We’re way too exhausted for that. We’re just working very hard for our artists, and we have to do what they need. We’ve only grown to fill that need.

Will you keep expanding in the near future, or stay the same size?

We don’t plan things that much; we’re just going with the flow. We do plan to open a kind of small bookstore and editions gallery, which has been a dream project for a while. It’s going to open next to us in this building in September. A lot of our artists are producing small editions, along with monographs or art books, so the new space will be a place to show those. We also want to be able to do lectures and artist talks there, to bring a criticality to the shows we’re doing.

Is there some through-line, some shared quality in the artists you choose to represent?

Well, there’s a regional focus to some extent. We like to find and promote artists from Chicago; it’s a big thing for us. We’re really proud of having found a program here and taking it global. Another area of common ground is that we’re interested in artists who develop a narrative through process. They’re very interested in the process of making things, and they make a hint of a narrative. Or there’s some personal statement that’s being made.

As opposed to something that’s purely abstract.

Right. Another area we’re interested in is artists with a little bit of a social practice, a social narrative—who are making, not so much a political commentary, but are looking at the world and responding to it. This September, for example, we have shows by Mickalene Thomas and Glenn Kaino. Both of them deal with issues they’ve been grappling with, including race, gender, political structures. Mickalene’s show is mostly done in cast bronze and has to do with her history with her mother, who was a flamboyant African-American socialite in the ’60s. Mickalene also produced a film about this, “Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman,” that was broadcast this year on HBO; the film will be shown here in the gallery. Also this fall we’ll be doing Glenn’s Leviathan, his first major show in many years, in the Elizabeth Street space.

Which artists have you had the longest professional relationships with?

Angel Otero, for one; we started working with him before he had finished grad school. Tony Tasset, who had a show here this summer, we’ve been working with for many, many years. We’ve added four or five new ones—including Mickalene, Glenn, Roxy, Jessica Stockholder and McArthur Binion—but most of our artists, we’ve been working with for close to 10 years.

Back in the days of the Hairy Who and the Imagists, Chicago artists had a kind of group identity, a set of shared aesthetic concerns, but that doesn’t seem to be the case anymore.

The good thing about being removed from New York or L.A. is that there, artists do tend to become slightly homogeneous; they develop schools that emerge pretty regularly, and the schools themselves push an aesthetic. Here, I think the artists don’t tend to group in those ways. Everyone has a unique practice, and we look at each artist as an individual here. I can’t think of anything that really ties them together, but I think that’s a good thing.

Kevin Nance is a Chicago-based freelance writer + photographer. Twitter @KevinNance1