Kohler: Preservationists of Art and Design

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

When I asked myself last winter where I should travel for a weekend away with my husband and children, I didn’t think about somewhere with an average temperature of 75°. I thought about heading to Kohler, an art-filled village in Sheboygan, WI just a couple hours drive from Chicago.

How did this sleepy Midwestern town by Lake Michigan become a center for art and design? Curious to know, I was happy to book an off-season room at The American Club, located half way between Milwaukee and Green Bay, in the heart of Kohler. Originally built as a dorm to house Kohler factory employees in 1918, The American Club, as it is known today, has been a five-star, five-diamond destination resort hotel since 1981, and it is just one of many Kohler company success stories. Located in the center of a campus that is home to four of the world’s best golf courses, one of the world’s best spas, nine restaurants and much more, the building itself, listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978, is a testament to how a company has stood the test of time by continuing to innovate, with quality and creativity at the center of everything.

*

The name Kohler is synonymous with plumbing, specifically: toilets, sinks and fixtures. A hotel stay at The American Club means as a guest you can “test-drive” Kohler products–a genius approach to brand-building. It was tempting to not even leave the hotel itself, but we were there for art. While exploring the campus I notice the very same materials utilized to make Kohler fixtures have been incorporated into various contemporary sculptures scattered around the grounds. Installed adjacent to the pool were over a dozen, glazed vitreous China waves by Natalie Clark. Tiny, colorful fish by Carlos Alves also swam among the pool deck's white wall tiles. An expressive cast iron figure, by Steve Bradford/Martha Heavanston, was placed along the path into the tennis center. Each work I saw was by an artist who had been a resident of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center's Arts/Industry program. These weren’t works purchased to furnish a resort, they were a permanent investment in artists made real, showcasing the visions artists bring to life when given meaningful support and access.

Not all the art on view was installed around the resort. The Kohler Design Center is a destination in its own rite, and it’s open to the public, as well as members of the design trade. Here, Kohler fixtures, including cast iron bathtubs, commodes and pedestal sinks are artfully displayed–including on the center’s famed “Great Wall of (vitreous) China.”

The basement of the Design Center features a museum about the Kohler family along with an overview of the Arts/Industry residency program, which was conceived in 1974 by former John Michael Kohler Art Center (JMKAC) Director Ruth DeYoung Kohler II. The program is both unusual and obvious, in an ‘A-ha!’ kind of way.

Arts/Industry offers artists time and space to focus on the creation of new work while in residence at the Kohler Co. factory in Pottery and /or Foundry. They are not limited by their medium–experience with clay or metal are not prerequisites. Much of the residency is technical, but what may begin as utility can spur creative thinking, and maybe a little bit of magic.

*

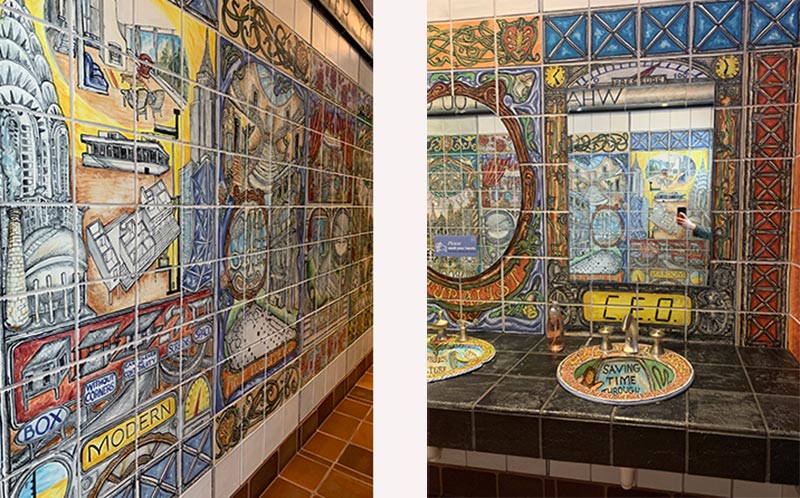

After visiting the Design Center we drove a couple of miles to the John Michael Kohler Art Center, an art space founded in 1967 that hosts extensive programming and exhibitions. At the front desk the staff reviewed photography protocols with us and then made a point of encouraging me to stop into each washroom on site. I was glad they did. In the late 1990s, JMKAC commissioned six artists to design, create and install the tiles, plumbing, and other components of the art center's bathrooms, using these immersive hybrids of public and private space to convey the belief that art can rouse you from routine. Cynthia Consentino’s The Women’s Room is super girly – a physical top ten list of feminine stereotypes depicted in over 120 glaze paintings: lacy undergarments, hats, shoes, bras, stockings, jewelry, and handbags.

On the other side of the Center, entering Merrill Mason’s Filling and Emptying you are greeted by grooming objects that have been cast in iron and tucked into marble nooks: perfume bottles, delicate gloves, fragile hand-mirrors and combs, each blackened and weighted like they could be effective weapons, if they weren’t used to prep for a fancy dinner party. These spaces, usually private and reserved for necessity, challenge not only the idea of objects and places we take for granted but also what a center for art can offer its artists, as well as the visiting public.

*

While the focus of the Arts/Industry program is innovation today, another separate area of focus I discovered at JMKAC was the preservation of overwhelmingly expansive but undoubtedly mind blowing world of art environments, folk architecture, and collections by self-taught artists. An incredible number of such environments have been preserved and now conserved and publicly displayed, thanks to the work of Ruth Kohler, who led JMKAC and pioneered its focus on Art Environment builders. Ruth died in late 2020 and was instrumental in providing the leadership and vision that has brought JMKAC to a preeminent position in the field of art environments. In 1983 when Ruth encountered the life’s work of Wisconsin artist Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, just two weeks after he had died, she was compelled to find a way to bring the prolific artist’s body of work to be seen in its entirety. It was a tall order, but soon after the Arts Center acquired 6,000 objects, including paintings and bone sculptures, marking the beginning of the Arts Center’s commitment to artist-built environments. It is one thing to seek out the best representations of an artist’s work, acquire them and make individual pieces part of a museum collection. It is another to track down, transport and reinstall thosands of expressions of an artist’s mind.

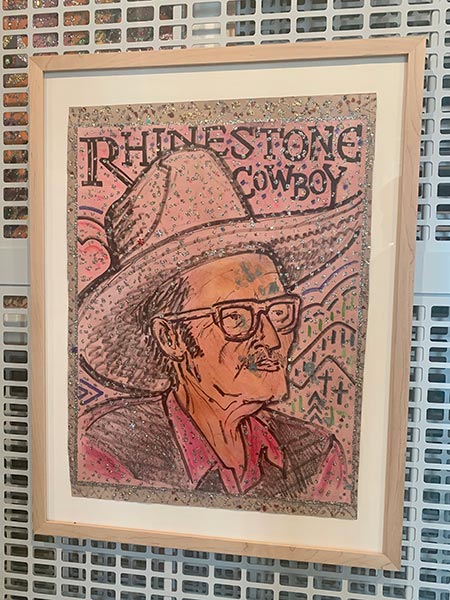

Following last summer’s opening of an extention of the JMKAC, The Art Preserve, a three-story space that is the world’s largest collection of artist-built environments, the Foundation’s efforts make it a national leader in the preservation of and respect for these collections. There has been a lot of attention on “immersive” art experiences recently, but so much of that has been virtual, digital or just made for Instagram. At The Art Preserve, you’re invited to immerse yourself in the artist’s world, where you can see wild visions in-person: Loy Bowlin’s The Beautiful Holy Jewel Home from McComb, Mississippi is wallpapered in glitter and construction paper reminiscent of Moroccan tile; Von Bruenchenhein’s gold-painted chicken bone thrones are displayed, along with hundreds of the artist’s paintings; dozens of Dr. Charles Smith’s concrete and tile figures make up a sort of miniature army. Complementing The Art Preserve itself is the center’s website, which provides additional context as well as images of the artist sites as they originally existed.

I marveled at not just the obsessions of these individuals but the sheer scale of the institutional effort it must have taken to make these tableaux available to the public. It’s a one-of-a-kind experience to wind through Ray Yoshida’s recreated home and see his work, and that of his famous students–Roger Brown, Gladys Nilsson, Karl Wirsum and Jim Nutt–alongside Native American Kachinas, African masks, wooden figurines and folk art that influenced the Imagists. All of this is presented without typically verbose explanations, only identifications–another sign that this is an altogether different place with entirely different art.

*

In 36 hours I completed a crash course on the Kohler family’s remarkable impact on industrial design and contemporary art. My experiences at Kohler were cohesive as well as disparate: an education on the large-scale weathered wood friezes of Bernard Langlais and his life in Maine followed a showroom viewing of a tower of sinks and toilets in every color. I played tennis in the morning and in the afternoon wandered through Emery Blagdon’s The Healing Machine at The Art Preserve. What began as a family getaway left an impression. Here, art informs everything and will continue to for generations, thanks to the success the Kohler Company and the Kohler Foundation are paying forward.

Publisher's note: This version of the article has been updated since it was printed in the summer 2022 issue of CGN to clarify that the Kohler Foundation and Kohler Company are separate entities from the John Michael Kohler Arts Center. The Kohler Foundation is a generous supporter of the JMKAC and its Arts/Industry program.