Hindman Celebrates Four Decades in Chicago & Beyond

By Anna Dobrowolski

Art auctions have a reputation for high-dollar headlines and cinematic cameos. You know the trope: something old and all-but forgotten is, with a final paddle raise and the help of a fast-talking auctioneer, someone’s ticket to early retirement. While that can’t always be the case (sadly), these auction fairytales remind us to pay more attention to our possessions. At Hindman, they have spent the last four decades doing just that.

In 1982, Leslie Hindman opened the doors to her eponymous auction house on Lake Street in Chicago’s West Loop. It grew to be one of the largest auction houses in the country. In 2018, Leslie Hindman Auctioneers and Cowan’s Auctions merged, and Hindman formed, with Jay Krehbiel at the helm.

Today Hindman Auctions’ operations are spread across 13 cities, holding over 140 auctions a year and looking towards a future in an increasingly global and digital market.

Despite Hindman’s physical presence across the country, Jay Krehbiel, Co-Chairman & Chief Executive Officer at Hindman, has not lost sight of the importance of digital technologies and reach in the auction world. In September, as a prologue to anniversary celebrations, one of their headlining shows will be a single owner, single artist auction of Chicago’s surrealist painter Gertrude Abercrombie. A strong digital presence will ensure that the sale of Laura and Gary Maurers’ Abercrombies will reach as many potential collectors as possible.

Krehbiel, who first got involved at Hindman through watching Leslie conduct her business, officially partnered up with her six years ago. He has since taken Hindman’s digital expansion to a far greater level. “Leslie was always thinking about introducing technology into auctions, a tradition bound, tradition-based industry. That’s something that she had been working on for a long time. Hindman was early to put their auction catalogs online, and what I try to do now is supercharge that. When the pandemic hit, we were in a much stronger place to continue business as usual,” he says.

According to Krehbiel, there are ways to tech-enable this business, but there’s no such thing as being fully remote in the auction room. Behind the scenes, the team handles every object in order to analyze its condition and present it to future buyers as accurately as possible.

*

When I called Zachary Wirsum, Director and Senior Specialist for Post War and Contemporary Art, he was at Hindman’s Lake Street headquarters, taking a break from curating the Cool for the Summer sale—the third in the summer series inspired by a pop song. Queueing Demi Lovato, the show channeled ‘cool’ with sizable abstracts and some household names such as Jeff Koons’ Puppy Vase; Salvador Dalí’s Venus with the giraffe; and Jane Hammond’s Love Laughs (1973). At the same time, Wirsum is looking ahead to the fall. He and Joe Stanfield, Hindman’s Vice President and Senior Specialist for Fine Art are co-head of sale for Casting Spells: The Gertrude Abercrombie Collection of Laura and Gary Maurer on September 28. Before the auction they will show the Maurer collection in Milwaukee and New York–both to expose more people to her work, and to pay tribute to the artist’s own roaming spirit and the friends she made along the way.

When the Hindman team is not actively sourcing art for an upcoming auction, art usually arrives from the ‘triple D’s’—death, divorce, and debt—or, more recently due to the pandemic, ‘deaccession and downsizing,’ explains Wirsum. It depends on the individual or institution.

Not all art arriving at the auction house involves stories of loss. Some buyers spend their whole lives pursuing their passion for collecting. Corbin Horn, Vice President and Senior Specialist of European Furniture & Decorative Arts, adds, “For people who are working to build up their collections, they consider selling a way to ‘trade up.’ When building a collection, many people don’t realize that you can’t just buy things at once. You have to spend your life buying, selling and trading up in terms of quality,” Horn says.

“One of the things we talk about at Hindman is that we believe that everyone is a collector at heart. These objects inspire people,” says Krehbiel. “If you don’t know where to start, everyone will tell you to start with what you love. The inspiration you have for the objects, and the passions you develop for the objects, will drive your curiosity forward and encourage you to learn more about the makers and their stories. So, buy what you love. It seems trite, but there’s truth to it.”

While the business is art and object driven, it’s people driven as well. Alyssa Quinlan, Chief Business Development Officer, tells me that her favorite part of the job is making connections with people and hearing stories, from a WWII fighter pilot to someone who has lost their spouse and sharing their stories through their art. “When people bring us the things they collected, it’s another chance to take a moment to reflect on how wonderful they were. There’s a lot more to it than looking at objects on their own. The emotional aspect and curating those collections means hearing their stories.”

Stories about what can show up at auction can also become fairytales. Here are a few recent ones the Hindman team members shared with CGN:

Jay Krehbiel: In 2019, we were honored to bring works to market for the Cranser family from St. Louis. They had, among other great things in their collection, two Calder Stabiles. We sold one for $1.9 million and a smaller one for $432,500. It’s exciting for everyone to sell big dollar items.

Famously, there was a 17th c. Chinese bowl from a North Shore Collection. The final price tag was $1.5 million, which was surprising, considering it was used as a bowl for car keys.

Joe Stanfield: There is one particular work of art I tend to go back to from maybe 12 years ago. A colleague and I drove to western Illinois and discovered what was, at the time, an unknown trove of watercolors by Wassily Kandinsky, just buried in a closet at this home. We took 60–70 unframed works on paper. We contacted one of the scholars in New York to authenticate the art, which were then flown to Paris and reviewed by a committee. It ended up being sold for $450,000.

Corbin Horn: The most unusual work of art that comes to my mind is an Andrew Clemens (American, 1857-1894) sand bottle that sold for $956,000. Clemens was a little-known Iowa artist who was deaf, and he made pictures formed by compressing colored grains of sand inside chemists’ jars. Remarkably, he made these works of art without glue and using only homemade tools. There are a few collectors in the U.S. who pursue these very aggressively. We have handled several Clemens bottles over recent years, and we have one (maybe two!) more coming for sale this fall.

*

Fairy tale or not, there’s no crystal ball to predict the outcome of an auction. So, what happens when a work of art simply doesn’t sell? It doesn’t mean that the previous owner had poor taste; sometimes it boils down to pure luck and timing.

“If on the day of the auction there just isn’t a buyer for an object, we either reoffer it for sale or return it. The auction industry is fascinating because the market is the global economy; different buyers are just there on different days,” says Krehbiel.

Delivering unfortunate news is a large part of the business, Stanfield tells me. “Most of us, including myself, think the work that we own is great. We are sentimental, especially with inherited things. I understand why people are disappointed. One of the handy things about auctions is that it is a fair market and the sales are transparent. We are able to pull up global data showing where the art is selling, and for how much.” The added transparency helps stymie disappointments and manage expectations before bringing a work into the auction room.

Technologies and tastes are bound to change over time. What ensures that an auction house like Hindman lasts is looking towards and embracing the future.

Under Gertrude Abercrombie’s Spell

A surrealist by any other name — known as ‘Mid-century jazz witch’ and Chicago’s Queen of Bohemia, painter Gertrude Abercrombie has long enchanted artists, writers, and musicians. To collectors Laura and Gary Maurer, who are offering up their entire collection of 21 paintings in September, she is simply known as “Gertrude.”

Abercrombie’s biography reads better than fiction. She was born in Austin, Texas, in 1909 but often traveled due to her parents’ careers at a traveling opera company (her mother, Lula Janes, was a prima donna). When Gertrude was four, the Abercrombies lived in Berlin until the outbreak of WWI. Forced to return to Illinois, they eventually settled in Chicago, where Gertrude would go on to study Romance languages and later work as a commercial illustrator designing gloves for Mesirow department store. It wasn’t until taking on commissioned work by the WPA in the 30s, however, that she decided to pursue art full time.

By then, she was a Hyde Park local, forging her own style in a studio on Dorchester Avenue near the University of Chicago campus. Walking past the heather-bricked row house today, you would not know this was where the magic happened–I didn’t. Those walls have heard the piano-tuning, rants, and laughter of musical giants: Dizzy Gillespie and Sonny Rollins, Pearl Bailey, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Max Roach. Where’s the commemorative blue plaque, “Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-1977) Artist, Friend, ‘Good Witch’ lived here”? Wrong Hyde Park, I regret to say.

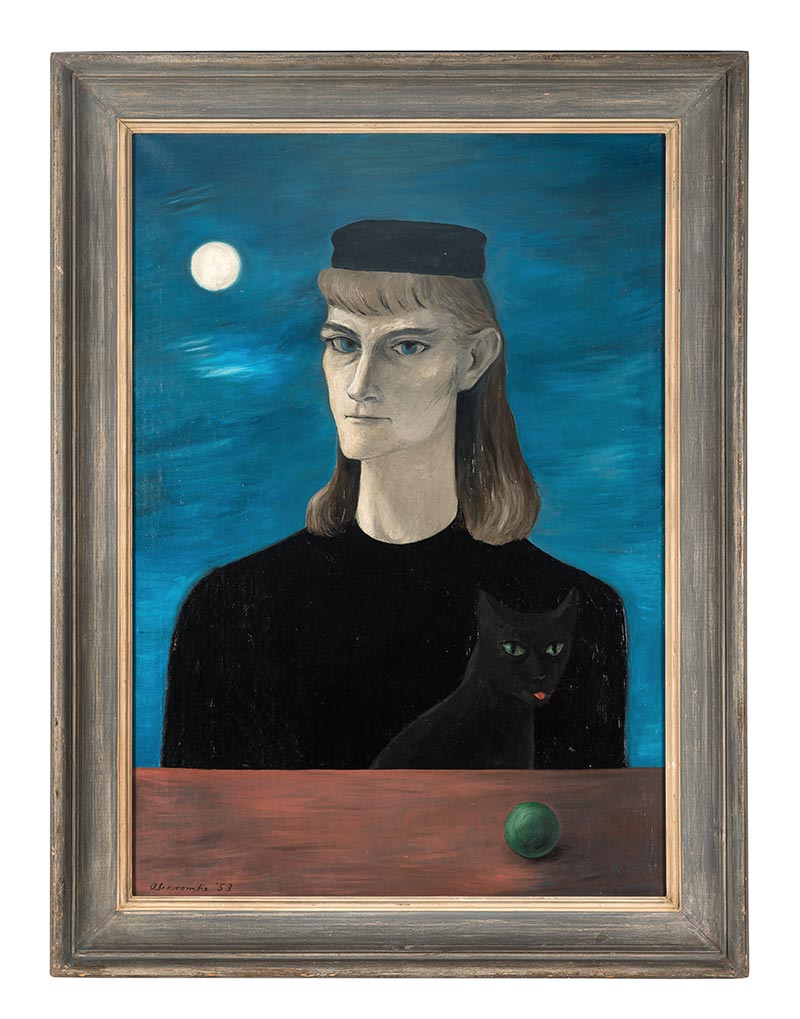

Surrounded by music and a lively cast of writers for most of her life, Abercrombie channeled her idiosyncratic artistic rhythm in easel paintings. Though Abercrombie never affiliated herself with any formal movement in modern art, she was labeled a ‘magical realist’ for her references to the otherworldly. Her subjects ranged from evocative, stark landscapes to still lifes with cats, owls, crystal balls, and shells. It’s unsurprising that surrealism’s vocabulary seeped into interpretations of her work–indeed, when she first saw the work of René Magritte, she called him her ‘spiritual daddy’ for sharing that same tendency for the absurd, illogical and dream-like–but her style remains a personal, psychological enigma. In essence, she painted from the reality she was most familiar with.

She painted self-portraits most frequently throughout her oeuvre and at various stages of her life. Her choice of subject matter, and the puzzling approach to them, earned her the title of ‘witch.’ (Who amongst women deviating from the norm - much less putting paint to it - hasn’t been suspected of sorcery?) In a 1977 interview with Studs Terkel, she mentioned that she was used to the moniker, once confessing to a group of children calling her a witch that she was ‘one of the good ones.’ Looking at her work, it’s impossible not to believe her. That was certainly the case for Laura Maurer.

*

Laura Maurer describes herself as “the kid who dreamed about being locked in a museum after closing time and living among all of that great art.” She knew art would always be a part of her life—a fact that her husband, Gary, understood was non-negotiable.

She first encountered Abercrombie’s work in the ‘90s on a trip to negotiate contracts in Springfield, IL. With time to spare, she walked over to the Illinois State Museum, which had Abercrombie’s paintings on display. There, Maurer had the museum to herself.

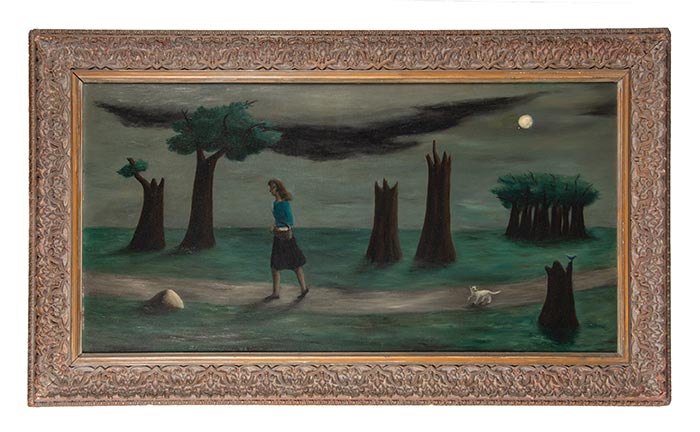

“Mesmerized doesn’t even come close,” she tells me over the phone, “It was love at first sight.” Through library searches, she found out that Robert Henry Adams Gallery had more Abercrombie paintings available. “I went up to Robert Adams, and said, ‘I’ll take it.’” The painting in question: Abercrombie’s Solitude. In this moonlit landscape, a woman is mid-gait, walking along a gray footpath amongst sparsely spaced trees. Behind her, a white cat glances back towards the distant forest. “While Laura fell in love at first sight, my appreciation [for Abercrombie] developed more gradually,” Gary Maurer adds. “After I spent some time with the painting, I found myself wondering, what was she thinking or going through at the time.” Both agreed that Solitude would be the start of their collection.

For the Maurers, searching for Abercrombie in local art fairs, estate sales, auctions, and galleries decades-long search was just as exciting as the acquisition. One of their most memorable discoveries was finding her self-portrait–which, at 34 x 24 inches, remains one of her larger works. “When we found her self-portrait with Possim, it was better than a million photographs. Much of her work was her searching for herself. Occasionally she would appear and become recognized as an element in some of her work. When this self-portrait became available, it spoke to her inner life and what she thought of herself.”

The thrill of discovery propelled the Maurers’ decades-long quest for Abercrombie’s work. So, how does one part with a collection after so many years? “It was time for these works that have lived with us over the years to be with other families or institutions so that they can live with Gertrude, like we have, for the last 30 years,” says Laura.

*

Preparing for a sale such as this takes a village of experts and specialists who are able to first authenticate the art, write detailed condition reports, set the starting price points and of course bring it to a wide market of interested buyers.

Chicago-based Hindman will be handling the sale of the Maurers’ beloved pieces this fall, while at the same time celebrating the auction house’s 40th anniversary.

#