MCA's 2024 Visionary Luncheon Honors Artist Sarah Sze and Key Museum Supporters

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

On Monday October 7, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago’s Board of Trustees and the MCA Women’s Board hosted the MCA Chicago Gala Visionary 2024 at The Four Seasons Hotel, Chicago.

The luncheon is an annual celebration of leadership in the arts and featured a dynamic conversation between renowned artist Sarah Sze and the MCA's Pritzker Director, Madeleine Grynsztejn. At the luncheon, attended by nearly 350 arts industry leaders and supporters, collectors, board members, as well as civic and corporate leaders, the MCA presented the 2024 Arts Philanthropy Award to BMO Bank N.A. for its exceptional support of arts education in Chicago. Mr. Darrel Hackett, President, and Chief Executive Officer of BMO Bank accepted the award on behalf of the bank. Additionally, the award honored both Mr. Hackett and his wife, MCA Trustee Nickol Hackett, for their generous philanthropy in our city.

In addition to being one of the fall season's highest profile arts gatherings, the Visionary luncheon plays a crucial role in supporting the MCA's commitment to learning and public programs. Each year, thousands of young people from across Chicago visit the museum to engage with contemporary art and explore its broader historical, social, and cultural contexts. The MCA raised over $640,000 dollars at the event in support of its Learning programs.

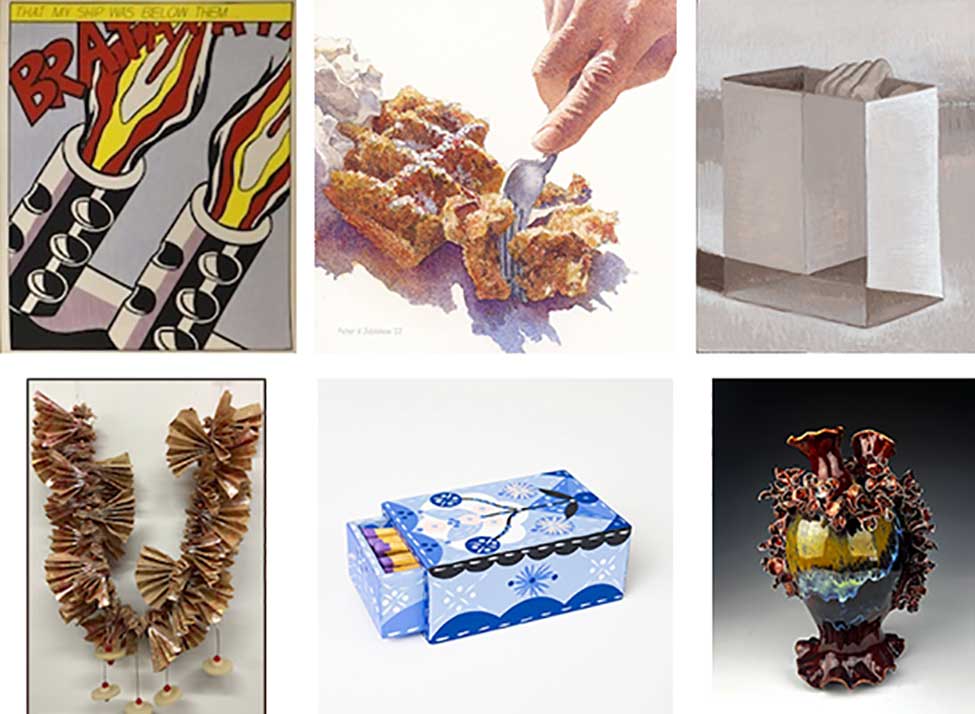

During their extensive conversation, Grynsztejn and Sze discussed Sze’s painting and sculptural work, how the MCA was her first institutional solo venue, and how artists and museums work together to create an artistic experience for the viewer. Sze's career has spanned three decades, but her creative perspective on technology and art continues to evolve. She notably got one of her early starts at the MCA, and at the luncheon Sze shared her own personal fondness for the museum, [The MCA] is a very special place. As Madeline said, it was here where I first did a show at an institution, and it was an incredibly warm institution. There are still many people on the staff who were there in 1999.

Sze's career has grown internationally since that first museum show, and she and Grynsztejn discussed how much the world has changed in the ensuing years, particularly when it comes to the accessibility as well as bombardment of images in our daily lives. At a time when everyone is a photographer, Sze has largely returned to painting.

The return to painting, she said, is about not representing reality, but really thinking about how we store images in our head. Since the late nineties, when I started making work, for all of us who have lived in that time period, we have been barraged by images in a way that has really changed the way we experience the world, the way we communicate. We're all photographers, we receive images at this incredible rate. I want to remind people about what we dream for, what we hope for, what we imagine. I want the paintings to be in this place when we wake every morning, where we've spent hours of our time making images in our head – that time where you are in this fragile moment trying to remember what your mind has created in the images, but you're moving into the space of the images outside your head.

Sze also still harnesses the ubiquity of images, merging the digital and the static in her public sculpture. Even the history of photography has influenced her current work. Sze explained, Most of the images that are in the paintings are actually stills from videos. So I think the static photograph is disappearing. Film was really started in the 1880s, and it came out of photographs – the photographs in repetition became the moving image. And now we rarely see images static. Our children are all pushing the button down and holding it and getting 20 images and choosing. Similarly in my work, they're mostly stills from video that I choose.

Dimensions variable. More info at victoria-miro.com

Grynsztejn drew attention to a work by Sze in Venice, noting for the audience the synthesis of a somewhat static grid holding pieces of torn paper onto which video is projected. Explains Sze, This idea reminds people that the digital and the physical are not actually separate. That everything outside our eyes is physical. In this work they're torn pieces of paper that you can imagine having in your pocket. Usually when we see a film and we forget the world around us. I'm interested in keeping you in this teetering place between what is the real and what is imagined. Floating images and space that we're navigating at this incredible pace is something I'm really interested in right now.

Continuing, Grynsztejn added, You've called these interior landscapes. The time of them, the experience of them is more like looking at memory than it is looking at reality. It's a nonlinear kind of experience. The writer, Sadie Smith, a really good friend of yours, recently compared your installations to being in an open iPhone that mashes up momentous and really incidental events.

*

Sze’s father immigrated to the United States from China and became an architect. She reflected that he probably would've been an artist, except that his family emphasized that he would have to get a degree or he would not get a job, or worse, no one would take him seriously in his new country. In the next generation, Sze grew up in Chicago looking at the world through the eyes of an architect in a modern city and understanding the potential to do what she wanted. That perspective of examining space and structure remains with Sze today.

When looking at images from Sze’s U.S. pavilion where she represented the United States of the Venice Biennale, Grynsztejn commented, “The thread that I think you may be picking up on directly, or even unconsciously, is that your work is both whole and made up of parts. Because of that sometimes, even though it is not the case in reality, it communicates the state of being barely held together. A consistent theme in your work is that vulnerability of the object, that fragility.” Grynsztejn continued, asking, “Why is that important to you? Why do you want to create that condition for us to share?”

Sze responded, “One of the primary ideas for me was how do you create an artwork that feels live? I think post COVID we've become more addicted to live events, to theater, to these shared moments where we feel things will never happen again. So [the work is about] how do you mark time? A birth, a marriage, a death – these moments are completely out of our control but they really mark what it is to be alive in this way that nothing else can, this kind of serendipity of process in the moment.”

Grynsztejn’s response spoke for the audience, “I think one of the reasons why I find your art so important and so gorgeous, but also so heartbreaking is because it reverberates with the transient nature of our own life, because it could so easily be forced to come apart.”

She went on to comment that part of what she loves about Sze’s work is how she actively compels viewers to care about what they are seeing. Through questioning how it is constructed, how long that process took, what is looks like from one side and then another, viewers are part of the conversation. They are being asked she says, “to gently to care for this work forever.” Or as long as we are each here.

*

Sze has a new permanent monumental work on view at New York’s LaGuardia Airport. She said she’s always getting messages from friends and family who take selfies near the work when they pass by. She also points out that while the work may look delicately suspended, it really is not. “The most fragile thing we have,” she says, “which I think is important for people to understand, is technology. The technology we have in public space as opposed to governmental space, it's already outdated. Think about how for museums, what they have to change all the time are the light bulbs, the cameras, the film. Now they have to tend to videos. They are [surprisingly] the most ephemeral things.”

We tend to think about videos that last forever – a moment captured and then shared digitally seems like it may never be erased. But installed in a museum or public setting, video and technology must be maintained and cared for in order to last. Sze made a surprising point in the 21st century, that paper is more durable than one would think, and that we also have centuries of experience preserving it. In the same vein, the work at LaGuardia may look fragile, but it is created to last, with images printed on metal and its structure crafted from industrial materials. This deceptive and chaotic digital and analog mashup, Grynsztejn points out, is actually what we all have been enduring for the last 15 years. Sze’s work shows where the physical and the digital are interchangeable and equivalent and here to stay. She is revealing the art history that we are all living through, whether we like it or not.

Sze admitted that she hates her phone and her attachment to it, but she knows she cannot live without it either, a sentiment that is entirely relatable. We know the pull phones have, the damage they can do as well as the access they can offer. The personal digital relationships we all balance are both fragile, formidable and changing fast.

Towards the end of the discussion, Sze talked about her students at Columbia University, where she is a professor. To emphasize her earlier point about how much we are accustomed to accepting digital images as reality, she talked about the disappointment many feel when they order art materials only to realize that when they arrive they are not what they expected. Often variances in color and texture leave them without the quality they expected. “They'll say, I want this to be fuzzy and red, and it's itchy and kind of purple. It's not the right thing. They're getting things digitally before they're getting physically,” she explains. It’s a lesson worth remembering.

There are plenty of chances to encounter Sze’s work in person. In addition to the work at Laguardia she has placed many works in public, very deliberately as Grynsztejn says, in zones of transit, such as subway and train stations, along New York’s High Line, and as outdoor projections on museums. Each work is accessible in this way is a democratic experience, says Sze. “We can spend all the time in the world trying to get people into the museum, but it is a building with walls. To put things into the public space where people don't need to know it's art, they don't need to know who made it, they can have an experience with it. They might be drawn in. The democratization of art has always been extremely important to me.”

More information about the artist Sarah Sze may be found at sarahsze.com and victoria-miro.com