Chris Craft: A Collector Discovers Friends and History Through Art

By ANNA DOBROWOLSKI

Picture being so close to a piece of art—no white-gloved museum guard barking at you to step back—that you could almost smell the coconut. Just by pointing a finger at the wall, an artist appears, espresso in hand, ready to answer your questions. This is not a fever dream, or a pitch for the next “immersive art experience,” but the home and art collection of Chris Craft.

Craft is a tech entrepreneur by day, and a self-professed ‘amateur’ art aficionado by calling. Though Craft considers himself a novice art collector, his collection is already outgrowing his Ravenswood home.

*

When I visited Craft at on a January morning, he was drinking coffee with Jabari Jefferson, a mixed-media artist from Washington D.C. As any Chicagoan could attest, a bleak mid-winter visit signals a true friendship.

“Jabari’s like a brother to me.” Craft says when he introduces the artist of The Library Series. “He was just teaching me about some art techniques. It’s how I like to learn about art.” It’s not unusual for Chris to talk about artists as though they are a part of the family. Each painting features a character, or a personal history, which anchors him to a specific moment in his life.

The three of us talked about how artistic talent, and by extension objects, gets passed down as we made our way to the piece that started it all: a sculpture by his father. “I started collecting as a tribute to him.” In 2017, he remembers visiting the Art Institute for the first time after his father died. While there he gravitated towards pieces by Matisse and Braque, colloquially known as ‘Picasso’s competitors.’ He stopped when he recognized Caravaggio by name rather than reputation. “That’s my stepbrother’s middle name!” he thought. Suddenly the fraternal association convinced him that art had always been a part of his story, and he realized he wanted to actively add to it.

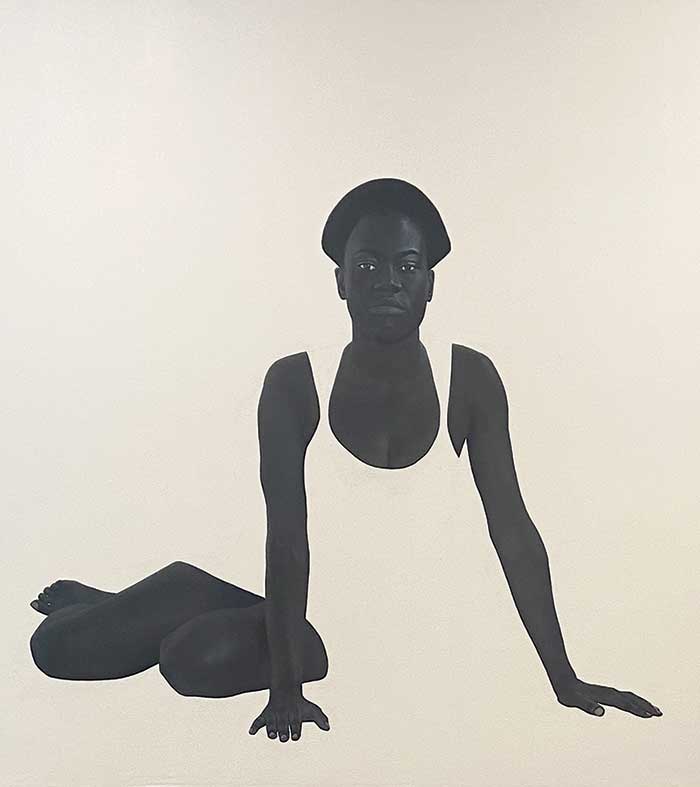

One of Craft’s first acquisitions, and the first painting that greets us in his living room, is Sungi Mlengeya’s Mdada. For the uninitiated, Mlengeya is a Tanzanian self-taught artist, whose mastery of minimalism and striking contrast is unparalleled. Mdada, the cool woman in the portrait, wears negative space well, making any viewer feel under-dressed. She seems at home in the Craft residence, as do his other 150+ pieces.

Across the hall we encounter Kajahl Benes’ Alchemist. The painting’s sculpted protagonist looks like he is carved out of onyx. He is caught in a moment of pensive illumination, interrupted only by Craft leaping onto the desk to point out the lustrous sheen of the painted robes.

Craft’s energy and appreciation for art and its history is contagious. When I ask him about his approach to collecting, he admits that he is still learning. Guided by intuition, this makes his collection more intimate– refreshingly less ‘branded,’ or motivated by boosting one’s portfolio. Yet it is still both business and personal.

If Craft is drawn to a piece or believes in its message, he makes the effort to get his name on endless waiting lists for art (these days, getting an organ transplant might seem easier than acquiring a coveted artwork). “I love living with art; it’s my own personal and emotional album,” he tells me.

Deeper into his home, Craft’s basement feels like an exclusive club. It’s also where we enter the ‘un-curated’ part of the house (the guest room has an 83”x 68” in painting by Aplerh-Doku Borlabi titled Tomboy. Doku’s ‘tomboy’ is literally made from coconut.) Here, we play the-floor-is-lava around an unfurled canvas that was just delivered—it’s a painting by London based artist Richard Mensah titled Hold On, part of his Why We Resist series. Mensah visually juxtaposes the 1968 Olympics medal ceremony in Mexico City with a cotton plantation.

My gaze moves from overseer on horseback to police car, cotton fields to polypropylene surgical face masks littered on the ground. Among them, I can see a poster of Breonna Taylor, captioned “Say Her Name,” that echoes a page from yesteryear.

As we move from the background to the foreground - past to present - the focus ends up on a young girl. Like Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, she charges ahead on her scooter, raising a Black Barbie donning Nigerian colors instead of a French flag. Her black sock quotes a new iconography that athlete John Carlos sparked when he took off his shoes at the Olympic ceremony. One wonders: if history is written by the winners, then who are the illustrators? Craft’s basement holds some of the answers.

*

Though Craft has had an eye towards preserving history through art for awhile, in recent years, it became important to him to find art that speaks to the times we are living in now. “I do not want these stories to be lost,” he says. His way of holding himself accountable and keeping the conversation going was to found the Black Collectors Guild, a network of collectors interested in supporting emerging artists while also helping each other navigate the nebulous world of art collecting. From conversations that have come out of the group’s time together, Craft has been able to fill his walls with work by artists such as Max Sansing, David Aplerh-Doku, Solomon Adufah, and Anthony Akinbola, to name a few. It is important to note that though Craft is refining his interests and building his art network, his tastes continue to evolve. At one point, he recalls, he was drawn towards bright colors and textures, seeking out Akinbola’s weavings of durags into artwork and Sansing’s saturated designs that can rupture monotony. Ismael Kateregga’s Nakawa Market Corridor even offered a kind of visual escape for Craft during a time when actual travel was not possible. “I wanted to be there [in that painting],” he explains.

*

As we wrap up our tour, Chris points back to Jabari’s Response of the Navigator (Library Series, 2021) and A Bright Future, They Say (Library Series, 2016-2018). Jabari says he had almost forgotten about the Bright Future piece, as it was a painting he worked on B.C. (before COVID). Each of these pieces seem to offer a snapshot retrospective of the artist’s own trajectory as he moved away from repetitive painterly strokes in favor of incorporating textiles, texts, and found objects. A morning spent discussing art felt familiar after so much time mostly isolated from others. Here a collector’s basement ends up being more than a place to look at art or entertain. It has becomes a place to leaf through books on African Art and debate where artists will go next. Here, fortunately, is where the man wearing white gloves waves you over for an opportunity to really get to know the art, an artist, and all the stories behind the scenes.