Jonathan Worcester: Painting with Creative Precision

Jonathan Worcester

By BIANCA BOVA

CGN: Thanks for taking the time out to speak with me Jonathan. I realize I’m catching you in the middle of a busy year.

Jonathan Worcester: Yes, absolutely. Recently I was in a group show at Old Friends called Ambulance Chase with Peter Fagundo and Michelle Grabner [n.b. curated by the interviewer, Bianca Bova], where I showed some paintings that were dealing in the genre that I’ve been working in for a few years now, but sort of thinking through them differently in terms of their contingency. Shortly I will be in a group show called Masterclass at Secrist | Beach that is a show of 25 years of painting alumni from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Then in April, I open a solo exhibition at 65Grand, Dead Reckoning.

CGN: The show at 65Grand, that is a new body of work that was conceived of for the exhibition?

JW: An entirely new body of work, yes. Everything is being made specifically for the walls of that space. I am measuring everything to the exact gallery specs. It will be a contiguous run of work with basically no space between the paintings, except where they meet the wall. It’s a horizon line of paintings. Everything is 48 inches high with different widths and different depths.

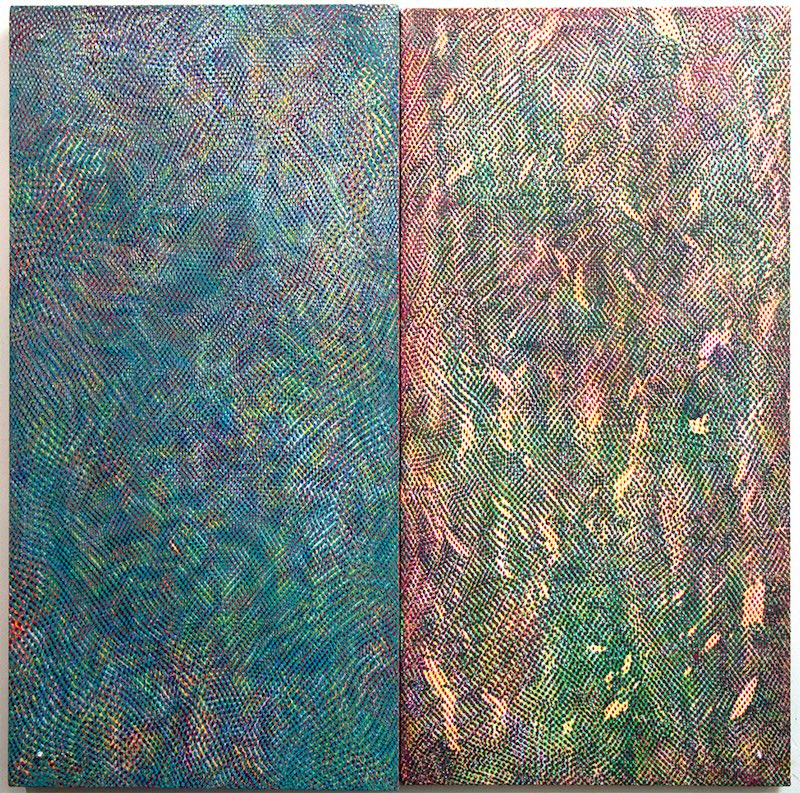

Jonathan Worcester, Untitled, 48 x 48 x 3.25”. Courtesy the artist.

CGN: Right now there is a resurgence among young artists for a number of reasons, ascribed to everything from the economic conditions of the day to this kind of a reverb off of the last 20 years of post-modern conceptualism, of a return to painting. Your work is often remarked on for being very process-oriented, which we see less of. I’m interested in what context you see yourself in given that assessment.

JW: Well, okay, thinking about process painting, I feel like there was such a resurgence of process painting that has been categorized through zombie formalism. I reject categorizing myself that way at all because I find maybe the least interesting thing about my work is the process. A lot of it is really just me sort of obsessively, episodically dealing in dots. And I feel like looking through the lens of process at the work allows for sort of this idea of labor being the most important thing that happens there, which is really not what I’m interested in. It becomes a simple solution for getting an understanding of a work without actually having to deal with the physicality of the thing itself. I don’t know, one of the things that I feel is fundamental in the aesthetics of “process” work, is painting that deals with the removal of the hand. That’s one of the things that is notably common among some of my peers in Chicago. I do feel like I’m a little bit on an island, though.

CGN: Knowing that, I’m curious what has your attention right now? What are you looking at?

JW: The work that I’m looking at and responding to is not really happening in Chicago right now. Except there was an exhibition in 1999 at Illinois State University that was called Post-Hypnotic. That was a seminal show that relates to the aesthetics that I’m interested in. It was curated by Barry Blinderman.

CGN: Oh, that’s a name I don’t hear often enough.

JW: The exhibition was a look at these aesthetics 25 years later, from a show at MoMA from 1965 titled The Responsive Eye that was dealing with the same thing. I picked up a copy of the catalog, and I’d actually be interested to talk to him as we’re 25 years later from his own exhibition, and see what he thinks about this sort of thing in the zeitgeist.

CGN: I’d love to know how that goes if you reach out to him. To pull back a little bit immediately from the work and go back to how you relate yourself to Chicago, you grew up here, didn’t you?

JW: I did. I was born in Milwaukee, but I moved here in first grade, and we moved to Hyde Park because my mom is a research professor at the University of Chicago. I left for New York for college and attended Sarah Lawrence, which is right outside the city, but I would do summers in Brooklyn. You know, served my Bushwick tour of duty.

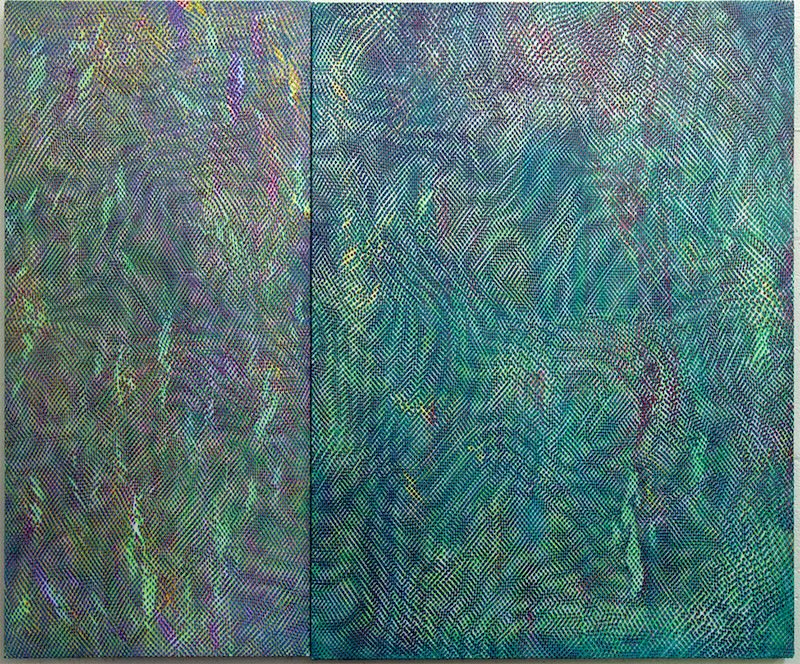

Jonathan Worcester, Untitled, 48 x 58 x 1.75”. Courtesy the artist.

CGN: As one does.

JW: As one does, or at least did in the mid-2000s. I love New York. I just needed to come back to Chicago for various life-oriented reasons. And I was having so much trouble actually making work in New York. Once I was out of school, and I didn’t have institutional resources, it was…I was painting on my roof. That was the only place I could get space. So moving back here has been great, because I’ve been able to have a studio all along. I was in the basement of a building in Logan Square, where I didn’t know if the tenants even knew I was there. But there was sort of an arrangement where I could use the basement and paint. I was down there in this windowless space for eight years. The rent was dirt cheap. I moved out because my desire for windows was strong, and the person above me was a religious zealot. They started having, I don’t know—Bible parties? All the time. And they were rowdy. It was so loud. Reciting things and slamming things on the floor. Now I’m in the 3200 Carroll Building with a number of good friends, people who I went to school with, and various artists at various points in their careers. I share a space with my friend Trey Rozell.

CGN: When you moved back, you also enrolled in graduate school at SAIC?

JW: I did, yeah. I was working at the MCA as a preparator and realized if I worked at the Art Institute, I could go to school for free on tuition remission. So I got a job at the museum as an art technician in the Collections and Loans Department, and then moved over to be the specialist of the European Decorative Arts Department. That’s where I still am. And went through grad school.

CGN: You also made your first foray into teaching at SAIC.

JW: I did, yeah. I was given a fellowship once I graduated to begin to teach a class there. And I taught painting practices. My time at SAIC was really affected by Michelle Grabner, and talking about pedagogy and sort of considering the way in which education, specifically higher education should work. I needed to try my hand at that. She put that bug in my ear. Having a chance to reflect on the way in which my education works and things that I wanted, and reacting to how students are now was really impactful for me in terms of thinking about how I create considerations in my own research. I’m grateful to have been forced to reckon with the way in which this thing should be done.

CGN: I’m deeply interested in something that I happen to know about your studio practice, a very specific form of passive media consumption. And that is that you are a habitual listener—not watcher—of Dateline.

JW: I sort of thought you might ask me about this. So, okay, full context. I work a nine to five job. I paint with an obsessiveness that requires me to basically be in the studio from 6 p.m. to almost 2 a.m. most days. I don’t have a lot of time for anything else. So I do audio books and I listen to podcasts to be able to feed the intellectual questions that I have. But yes, one of the lighter things I very often engage with is Dateline—I’ve more or less listened to its archive by now. The format itself is obviously made for television. It’s so funny they offer it in podcast form because they constantly refer to images and people. I think there’s always been a fixation culturally with true crime. And I definitely participate in that to a certain extent, but the reason I love Dateline is the format in which they do it is classic. They’re like the first true crime show and they still have these sort of network television personalities that are associated with it. Despite the uptick in interest in true crime, they have not strayed from their formula in the decades they have been on. It’s not a dumb podcast that’s more about the podcasters’ friendship, which I could not care less about, than the content. They explicate the thing thoroughly. They go through the entire investigation and there’s no frivolous conversation. It’s fact-based. It’s well-edited.

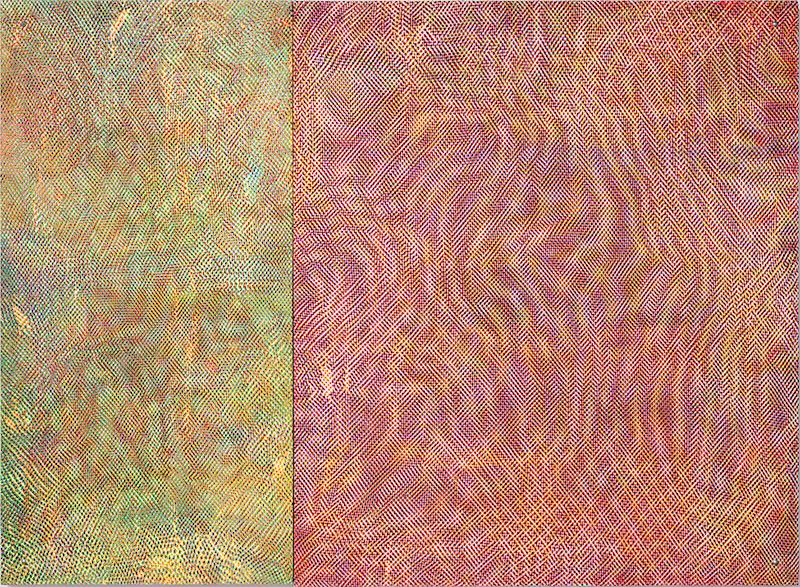

Jonathan Worcester, Untitled, 48 x 68.75 x 3.5”. Courtesy the artist.

CGN: This is what fascinates me—you’ve chosen a highly, highly, highly consistent and formulaic program to be the thing that you are passively consuming as you work. The relationship between that and the inherent obsessiveness of your paintings, both in practice and process, I would like to know more about that.

JW: Yeah, that’s a great connection. Actually that wasn’t obvious to me. So thank you. The way that I actually am making work is so scripted. I know how I’m going to do it, and from there it just deals with repetition, with patterning. The way I create difference is in semi-object-oriented things about the work, like changing the context, changing how they are contingent to the space around them. I can get so obsessive about color relationships. Just looking at a painting next to a painting that’s dealing in the same patterning and how much they affect each other—that’s what’s really been blowing my mind recently. But I am extremely formulaic. I think I’ve worked out a practice where I don’t have to stand back with my brush and feel this romantic trauma. I find that so obnoxious. I am not struggling. I’m having a great time listening to Dateline and I’ve baked in maybe ten decisions for each individual painting. Then I’m just working. And that is fun for me.

Dead Reckoning at 65Grand opens Friday, April 18, 6-9pm. On Friday, April 25, 6-9pm Frieze is hosting a private reception and exhibition viewing for EXPO Chicago VIPS.

RSVP to info@65grand.com

More information about the artist at jonathanworcester.com

#