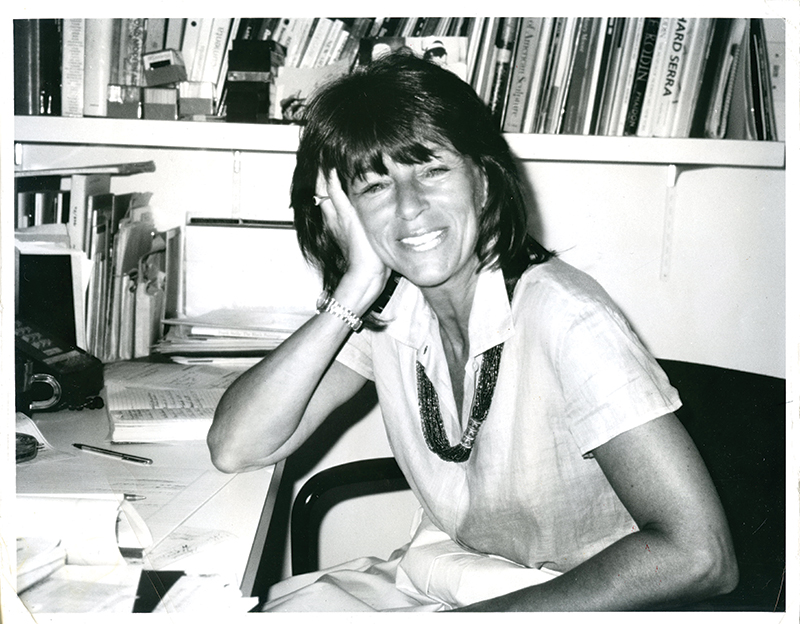

Connecting Change Through the Decades: Rhona Hoffman

Courtesy Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

By GINNY VAN ALYEA

Last October Rhona Hoffman announced that in spring 2025, when the gallery’s West Town lease at 1711 W. Chicago Ave. was up, she would close the physical space and begin a new chapter in the gallery’s half-century history. It was my hope upon planning this spring issue that I would have the chance to speak with Hoffman, who recently celebrated her 90th birthday, about her plans for what comes next and to hear her reflections on her remarkable, art-filled life and career.

When we met at the gallery in February, Hoffman was about to fly to New York for her gallery artist Amanda Williams’s opening at Casey Kaplan Gallery, having just returned from attending Williams’s exhibition opening at Spelman College in Atlanta. When I shared my excitement of catching up with her for a quick ‘exit interview’, Hoffman firmly let me know that ‘exit’ would be inaccurate.

“Exit is a full stop, so I’m not doing that,” she explained. “Segue is a much better term, as it implies a seamless transition within the gallery’s program.”

Hoffman is ready for this change from one stage to another. As she closes the gallery space, she is considering the variety of opportunities and ideas she has to remain active in the art world. Over nearly 50 years as a gallerist, she’s earned a distinguished international reputation, having amassed a remarkable amount of knowledge and experience about running a prosperous, influential contemporary gallery program. During our talk Hoffman revealed that her life in the art world afforded many surprising experiences through her connections and engagements with life in this industry. One example, she tells me, is that because of her early dedication to presenting women artists, and contributing to their equal representation, she was made an official, honorary Gorilla Girls member. After so many years building relationships and putting forth her perspective through art, having the art world acknowledge her gallery program, her artists, and her humanism, I can’t blame Hoffman for not wanting to say goodbye just yet. While Hoffman doesn’t know the details of what comes next, she does know it is not yet time to exit.

*

MCA Women’s Board members Helyn Holland, Dorie Sternberg, and Rhona Hoffman examine goods sold through the MCA Store. Photo © MCA Chicago

In the 1960s when Rhona Hoffman moved from the East Coast to the suburbs of Chicago, having studied art history at Vassar, she was looking for something to do. “I was married, having kids, and we moved to Highland Park. It was really boring. I found out that there was an organization called The Highland Park Associates of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). They tried to get people from the suburbs down to the Art Institute and connect them to the museum and to each other by hiring speakers once a month or so and inviting people. It was smart, but I remember I wasn’t that happy with what they were doing, so I joined the organization and I worked my way up to be president, so I could do what I wanted.” Hoffman’s initiative gave her some authority over the group’s programming. She wanted it to focus on more current happenings, what she considered interesting. She admits some of those gatherings weren’t enthusiastically received, so the organization didn’t want to formally host them at the museum. Instead Hoffman held them in her living room. “We had Arthur Siegel and Aaron Siskind together for a program, and we had professors from Northwestern [University], and critics like Harry Bouras [of Hairy Who fame].”

While impressing all the women of the board, including some fellow Vassar alumnae, Hoffman was recognized by many as a woman ahead of her time. Not only did she have a penchant for art, she could get things done. Hoffman says that was the beginning of her Chicago life in the arts. She joined the Woman’s Board at the Art Institute of Chicago, and soon after, toward the end of the 1960s, Hoffman was well situated in the Chicago art world as it was evolving. She was asked to be a member of the first Woman’s Board of the new Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), just as it was opening. Engagement with the MCA placed Hoffman in the front row to ground-breaking art and positioned her to gain business experience and meet more people in the contemporary art world.

The MCA, she recalls, was always ahead of its time, as well as also ahead of other museums at that time. “Jan van der Marck was the first director [of the MCA] and he was brilliant. His first show was Poetry to be Seen/Paintings to be Read, [which opened in the fall of 1967.] The next show he did was Art by Telephone.” Hoffman said she recently came across some information about the exhibition, which the MCA credits with being extremely influential in the museum’s early history. Art by Telephone asked artists from the United States and Europe to communicate their ideas for artworks over the telephone to MCA curator David H. Katzive. MCA staff then executed the works based on the artists’ oral instructions, avoiding all blueprints and written plans. After six weeks, all of the works exhibited in Art by Telephone were either destroyed or disposed of by the museum. Hoffman emphasizes the importance of how the exhibition helped the fledgling institution establish itself quickly. “This exhibition was at the MCA before it was at MoMA,” she says. “It helped the museum make a mark.”

Sol LeWitt installation at the gallery, 2010. Courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

The opportunity to make a mark appeals to Hoffman in that it is a form of public education, curating and presenting new ideas through art. We spoke about how there is a long-held myth in Chicago that the MCA was opened because a group of collectors were being kept off of the Art Institute’s board. When I ask Hoffman about this she responds, “No. There was a group of people interested in forming this [new museum.] There were some great collectors here–the Shapiros, the Hokins, the Bergmans and the Horowitzes. They knew what they were doing [starting the MCA]. And it wasn’t because they weren’t admitted to the Art Institute. They didn’t want to do what the Art Institute did, they wanted to do what they wanted to do.”

The distinction is an important one that corrects a story that implies one group of collectors didn’t measure up in comparison to another, and that given their choice they would have joined AIC’s board. As Hoffman explained to me, Chicago’s art collecting landscape was changing. On one hand, within the city’s collector community there was of course interest in remaining affiliated with AIC, one of the world’s most famous museums, and, “On the other hand,” she says, “the Art Institute wasn’t going to have Art by Telephone. One institution can’t do everything.”

It would take an entirely new museum to make it happen.

*

Works by Leon Golub on view at the gallery, 2017. Courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

Hoffman’s connections and experiences led from one role to another. It was on the MCA board that she very successfully launched and ran the museum’s store, one of the first in the country, with Helyn [Holland] Goldenberg for a decade, proving that a commercial space in a museum would benefit the MCA’s bottom line by becoming one of the most popular shops in the city. She was also becoming a collector. “Even when I moved from New York, I remember the first thing I bought was a work by Richard Hunt from Bud Holland in a parking lot. In 1961 the second piece I bought was a painting by Leon Golub for $2,400 from Allan Frumkin. I paid that off in a year.”

Energizing organizations and learning what made certain boards tick led to both friendships and knowledge. “An older board member explained the Women’s Board to me, ‘My dear, one third of the board is here because their family is important. Another third is here because they give money. And the other third is us. We are the worker bees.’ So that’s how I learned what the board was about.” Working alongside other women would eventually help Hoffman in her biggest move yet.

A surprise professional opportunity followed a difficult divorce. Hoffman recalls, “The divorce was good for me, but bad financially. It helped that I had been collecting art, and all the dealers were my friends.”

“My friend Grace Hokin had two galleries at the time, one in Bal Harbor in Florida, and one on Ontario Street [across from the MCA]. She called me up, ‘Oh, I’m so glad you got divorced, finally.’ Then she said, ‘I’m so sorry you’re poor. Come and be the director of my gallery.’ This is literally how my career started.”

Hoffman was incredulous, telling her friend she had never even thought of running a gallery. Hokin persisted, “She said, ‘Oh, come on. You went to Vassar. You studied art history. You know all the collectors in town. I’ll teach you the rest in 10, 15 minutes.’” Hoffman accepted her offer to make a new start and now admits she knew she could help Hokin become a contemporary art gallery.

*

A few years later, in 1976 she and Donald Young opened Young Hoffman Gallery on East Ohio Street in the Ontario/Michigan Ave. area of downtown. It would be several years before they relocated the gallery to what would become River North. “I knew other galleries that had been operating in Chicago for a while, but for our first couple of shows, we really felt that we had to catch people up. We had an exhibit of prints from [New York dealer] Ronald Feldman’s Parisol Press. Many became our gallery artists–for example Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, and Donald Judd. We wanted to show art that was contemporary internationally, without regard to location.”

“One of the things that helped us was our informality. The table we used was a butcher block. On Saturdays all the collectors came and we just sat around and talked about art. We were very accessible, and we were happy to have people with us.” The scope of the gallery continued to expand, and the city’s collector base increased as well. “It wasn’t just me and Donald,” Hoffman notes. “We had the Renaissance Society, Phyllis Kind [and the Hairy Who], Richard Feigen. We had a lot of help in terms of becoming contemporary, staying contemporary, being supported by people who liked it and understood. The collector base was spectacular. And because it was a small [community,] everyone knew each other and also wanted to help.”

Hoffman sees the history of Chicago’s art world at that time as one of collectors making choices, with museums running to catch up. “In the 19th Century, it was collectors [traveling Europe] who made the Art Institute take all those paintings they said they hated [but which made the museum famous]. That was so Chicago, even then.” She shares a story from the time of Young Hoffman Gallery, when a call between friends before a trip to New York resulted in some unique carry-on luggage. A well-known collector asked Hoffman and fellow MCA Board member Helyn Goldenberg to bring back a Joseph Cornell box they had just purchased, instead of having it shipped. Hoffman says it was just like any other flight, except she held a fragile, avant-garde artwork on her lap for a couple of hours. That sort of informality was so cozy, she remembers. “It was sort of strangers becoming friends.”

*

Michael Rakowitz , The Flesh Is Yours, The Bones Are Ours, 2016. Courtesy of Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

The gallery’s legacy and Hoffman’s own name ‘Rhona Hoffman’ are the amalgam of her dedication, integrity, expertise and care for the many artists Hoffman has worked with, exhibited and represented over these many years. She has championed and given visibility to dozens of artists. She has launched countless careers from the very beginning and developed many others. She doesn’t hesitate when I ask which single artist, out of such an esteemed group, she thinks has represented the gallery’s mission most purely. “Sol LeWitt. He was a great artist and a lovely man.” The two were friends and kindred spirits, with Hoffman noting she considers him the greatest artist ever (Hoffman added two more ‘evers’ to her adulation). LeWitt was political, she says, not necessarily in his art, but in his life. He was also known for his generosity, trading with artists he admired the most. “He’d ask, ‘Do you think Lorna Simpson would want to trade with me?’ It was his way of admiring another artist. So he had this huge collection of work by artists when they were young.” Hoffman shares that when the gallery started showing [photographer] Dawoud Bey’s work, around 1993 or ’94, LeWitt and Bey both happened to be spending time at [Phillips Academy] Andover in Massachusetts. Bey told LeWitt he wanted to take his picture. LeWitt said he didn’t want to, but [his wife] Carol said yes. Months later, a truck showed up at Bey’s house on Chicago’s South Side, and in it was a very large-scale drawing from LeWitt; unexpected artistic reciprocity.

Artists’ mutual respect, connections and friendships have contributed much to the gallery’s program. As Hoffman says, it’s quite common for one artist to lead to another. If you tried to create a family tree of the gallery’s stable, there would be many branches. Though rooted in conceptual and minimal art, the gallery has also stayed available to emerging ideas and always had a socio-political branch. “I’m very hyper-political, so a lot of the gallery’s artists are artists who were, while not totally political, at least socially political.” Hoffman says the relationships that develop are important for her to genuinely share each artist’s perspective on the world, and to communicate what their art expresses. When I mention the work of Iraqi-American gallery artist, Michael Rakowitz, Hoffman says, “He and I have been together for years. I adore him. I love his brain. I love his mind. I love the work that he creates.” Many years before Rakowitz, Hoffman says, came Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, whose work she first exhibited in 1982. “It’s a clear line from them to Michael. It’s not a big jump. It’s about being connected, and I like being connected to the world through art. Art changes people and art changes countries.” She points out that Golub and Spero examined the violence of the Vietnam War, and Rakowitz has explored the Iraq war, and beyond, because war is a constant. “Art has always jumped into the fray to answer war. And artists are always on the right side of destiny,” Hoffman says.

Hoffman’s artistic relationships go back decades, but she’s also known for continually adding to the gallery’s program by bringing on young, new talent. “I always go into that with happiness,” Hoffman says. One artist she brought to the gallery’s roster around 2015 was Nathaniel Mary Quinn. “I got a phone call from Jessamyn Fiore–the daughter of Bob Fiore, the photographer for artist Robert Smithson. She said, ‘Rhona, there’s an artist I just found. I think you will like him.’ She sent me a little picture. I was going to be in New York the next couple of days, and I went straight from the airport to Quinn’s studio. I went in and I saw the work. It was a teeny house, and it was breathtaking. It was so exciting to see someone of such big talent and ideas. I signed him up right then and there, and we had a show that year in September. Some things take time, some things don’t.”

Hoffman has trusted her eye as much as her connections over the decades. She has discovered many artists and introduced them to collectors. She’s also blunt about others in the art world who keep an eye on what she sees first. “I’ve lost a lot of artists because they get picked up by mega galleries in New York and LA. They go shopping in my store. I know most of the time, that’s the way of the world. It happens.”

*

Courtesy Rhona Hoffman Gallery.

Last October Hoffman announced that the gallery’s lease was up in April 2025 and that she did not plan to renew it or relocate. “I love art,” she says. “I’m going to do something, maybe something smaller. But I need to think. When you do something for 50 years, you get up and you go to work. And it’s easy. I think that really, it’s a wonderful thing.” She admits she’s torn between loving what happens in a gallery and also not wanting to come to work every day anymore. She turns to me and mentions the lyrics from a song she can’t place, “I got to go, but I don’t want to go.”

In 2014 Annie Leibovitz photographed Hoffman for Vanity Fair, when she was named one of America’s superstar female gallerists. And she’s sustained that elite status through the decades. There is only one Rhona. But being the only one has its limits where there are only so many hours in the day. As she considers what is next for the gallery and for herself, Hoffman says she is thinking about how to do all she wants to do. How to best spend her time weighs on her. She refers to a local organization benefit invitation the following week and laments, just a little, that she can’t make it. Instead, she says, she has to fly to New York for gallery business and she will also attend the Human Rights Watch dinner, of which she’s on the board. “There’s just a limited amount of me. So I make some choices about what I can still do.”

“I think coming to work, like yesterday, is fun.” She shares that the day before, Art Institute curator Melinda Watt, who is working on a Claire Zeisler exhibition, stopped by because Zeisler was a friend and artist at the gallery. Hoffman describes how they got all the artist’s books out and “made a mess,” excitedly describing the energy that comes from hosting visitors, and talking and searching for information. She says they even decided to order pies from Hoosier Mama down the street. When Hoffman offered to let Watt take the books needed back with her, Watt said she’d much prefer to go over them at the gallery. Hoffman was delighted. Next a collector arrived, another old friend. “It’s like having a town hall,” Hoffman says. “Being a meeting place is something that I seemed to be able to do easily.”

Now 90, Hoffman is contending with an increasing awareness of mortality and viewing her time as a limited resource. She wants to stay involved with art but also to respond to a fraught social and political climate. “I’m still pretty healthy and I don’t break and rarely get sick. I’m planning to stay in the art world but would also like to put more of my energies into what’s happening in the larger world that is so distressing, to do more work towards human rights. I’m ready to do whatever needs to be done, even if it’s writing letters and sending postcards.” Hoffman knows the relationships she’s built with her artists, collectors and institutions in Chicago and beyond will exist beyond the gallery’s walls, as they have always been intertwined. The gallery was not just a job, it has been an expression of herself and her life.

#