Yvette Mayorga: Artistic Confections Add New Layers to Art History

By ALISON REILLY

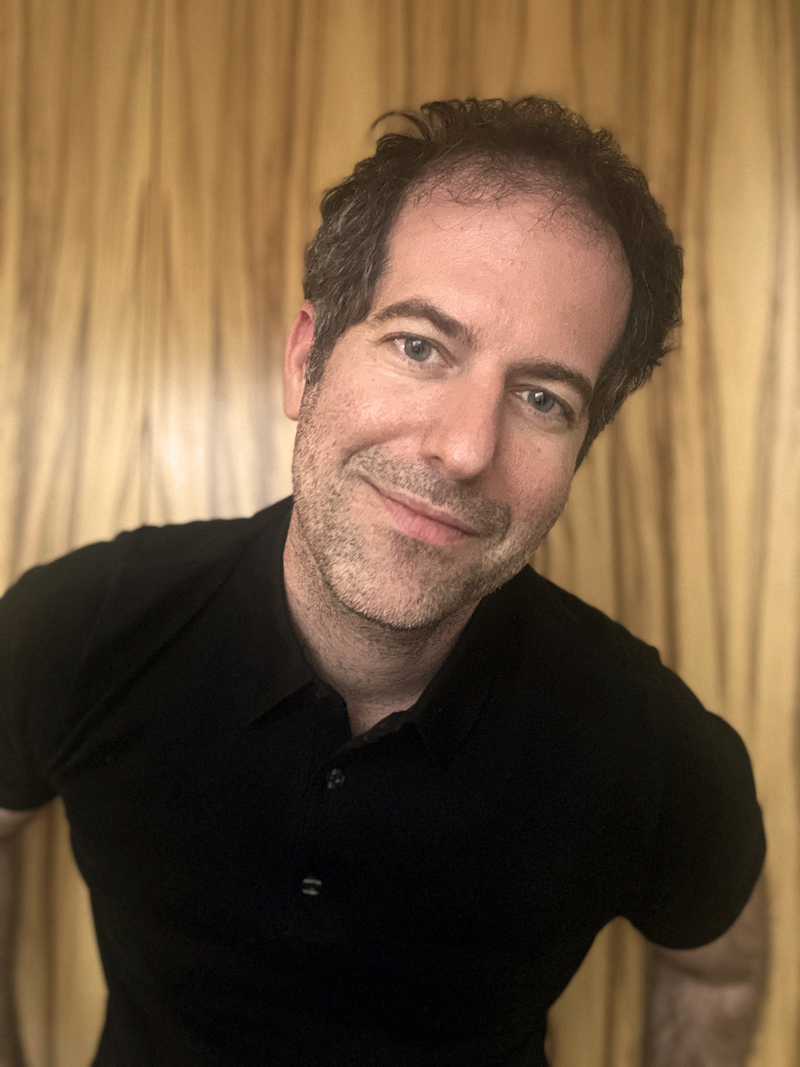

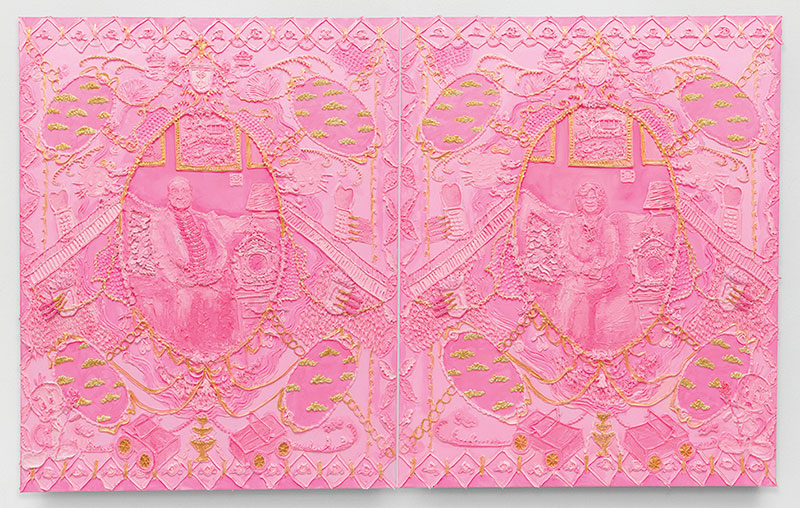

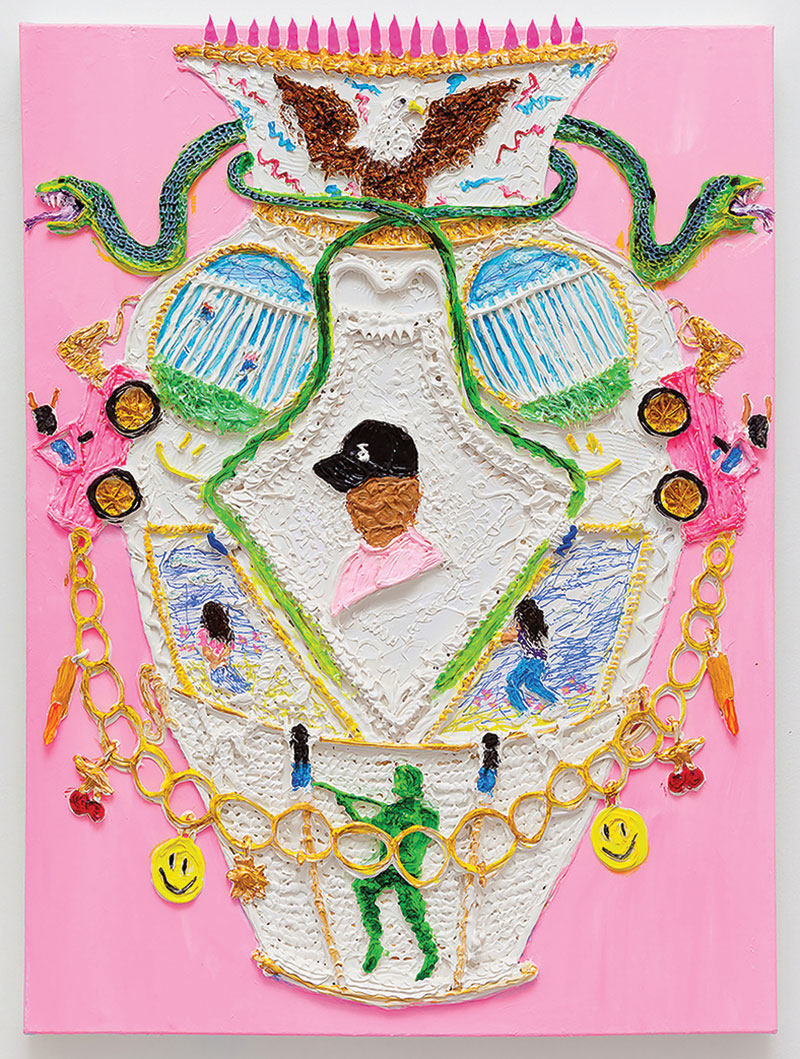

Treating paint like frosting on a cake, artist Yvette Mayorga pipes saccharine landscapes onto canvases. Littered with pink cars, empty Cheeto bags, smiley faces, and references to ICE and Homeland Security, her paintings tell a truth that may be hard to stomach: the American dream is making us sick. Mayorga has been working with these motifs for several years, but the ongoing pandemic confirms what she has hinted at all along—that the promise of a better life in the United States may come with a number of severe consequences. Mayorga’s paintings, featuring fluorescent colors and soft textures juxtaposed with military figurines and blurred faces, are jarring portraits of America in 2020.

Over the past few months Mayorga has been preparing for a number of exhibitions including LatinXAmerican at Depaul Art Museum, which opens in January 2021 and ESTAMOS BIEN: LA TRIENAL 20/21 at Museo Del Barrio in New York. She was recently selected as a finalist for the 2020 Artadia Chicago Awards.

CGN: First, how have you been doing these past several months, and where are you working from?

Yvette Mayorga: It’s been difficult to see my community and family members be put at a higher risk due to COVID-19. I had the privilege of shutting down my studio at MANA and being able to work from home for most of quarantine, but of course many essential workers didn’t have that choice and continue to be put at risk. Once the guidelines were lifted a bit in July, I returned to my studio while practicing social distancing and safety guidelines. It’s definitely been a lot of ups and downs and check ins with friends and family to make sure everyone is holding up and remembering we are strong as a community.

CGN: How has your practice changed since March when the stay-at-home orders were put into effect?

YM: Quarantine has affirmed what some of us have already known—that there is still work to be done in rewriting Art History due to COVID-19’s disproportionate effect on people of color and immigrant communities. I plan to continue to share the untold stories in my work with frosting through my feminist perspective.

CGN: What is a typical day in your studio like?

YM: A typical day in my studio includes an iced coffee, playing some Buscabulla, and beginning by catching up on some art admin emails/inventory/contracts for the first hour, then I do any research/source image printing related to the work I’m working on, and then I begin mixing my colors for piping. Some days my order of doing things changes, but usually it’s in that order, because it makes me get emails out of the way so I can focus on my favorite part, which is the creating.

CGN: When did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

YM: It’s something that my intuition has always told me to follow, although during high school I did consider different creative career paths, such as fashion design or interior design, but I was always pulled towards painting. I definitely think growing up with siblings who were great at drawing and were always being creative around our house made me think there was a possibility in art. It also helped that my high school art teacher gave me advice and tools to think about art as a career, because I didn’t know anyone who was an artist—and that’s really integral to seeing yourself in a field—if you don’t know anyone doing your dream job, it takes more of a risk to follow it.

CGN: I read that you initially used baking frosting in many of your paintings and sculptures but have since changed to acrylic to ensure the longevity of your work. How have other aspects of your practice changed over the past several years (conceptually or physically)?

YM: I used to source frosting from bakeries who had buckets of leftover frosting that was going to be discarded. I really enjoyed seeing all the different colors and decorations mixed in the tubs that gave me small glimpses of maybe who those cakes were being made for that weekend. Most of my “Monuments” series are made with real frosting, and, of course, frosting decomposes after a certain amount of time, so I went back to paint but with a more sculptural approach, where I used traditional baking tools to do the painting. That was more exciting to me than traditional painting—I think it’s the sculpturally-inclined part of me that loves to see texture and relief on any substrate.

Conceptually my work continues to naturally evolve as one research topic leads me to another and another and so on. The content is all pertaining to one grand idea, but the idea is so complex and has so many layers I still am barely touching it—that, to me, is exciting.

CGN: How did you decide to incorporate confections, cake decorating, and pastillage into your work?

YM: I first wanted to address the decadence attributed to the American dream and consumerism, while referencing my mother’s labor – in the ‘70s she worked decorating cakes at Marshall Field’s. I began using real frosting to reference both themes, and now I am also incorporating references to the Rococo style—everything is tied to ideas of labor, gender, architecture, and colonialism under the big umbrella of American idealism that is placed on immigrants.

CGN: Tell me about your experience growing up in Moline, Illinois? How has that informed your work?

YM: My experience growing up in Moline was mostly great. It’s a small city where everyone you go to kindergarten with you also go to high school with. I grew up surrounded by my family and a tight knit community. I also felt like I partially grew up in Zacatecas and Jalisco, Mexico where my family and I would travel to every summer until I was about 18 years old to visit my grandmothers. I think the experience of being in two countries as a child really gave me a transnational perspective that allowed me to understand my parents’ stories of growing up in Mexico and to shape my understanding of my identity. I am grateful for my parents to have given my siblings and me that experience, because it has made me who I am today.

CGN: What impact has Chicago had on your formation as an artist? What is your relationship to the city?

YM: Chicago was where we would visit my aunt as a child and also a place filled with memories of my parents’ time here in the seventies, as it was one of the first cities they immigrated to. There is a lot of my familial labor history embedded in the South Side of Chicago that reminds me of what it must’ve been like for my parents to begin their life here. As an artist, it’s where my community is.

CGN: I was looking at your Instagram and saw an adorable little puppy. Can you tell me about your dog?

YM: Roco (Rococo) is our new family member, she is a Victorian Bulldog. My partner and I decided it was time for a happy addition during quarantine, and she’s really brought us light during difficult times.

This interview is featured in the fall 2020 issue of CGN. To receive a print copy, please subscribe for $20/year!