Catching up with Candida Alvarez

By ANNA DOBROWOLSKI

Who’s afraid of Picasso? Many artists love to hate him—his audacity, controversial personality, and, we daresay, knack for abstract have earned him a spot in the “one-name-only” hall of fame. Candida Alvarez, through her dazzling configurations, shows us that associating Picasso with mosquito bites is just one way to upend the canon.

As we learn in a recent conversation with Alvarez, Picasso is yet another source to be reckoned with, and further proof that to survive as an artist we don’t always need to start from scratch. Sometimes we just need to scratch the surface.

*

New normal is a funny thing. I caught Alvarez adding colorful daubs to a canvas (I, a floating head on her screen, and she, wearing a yellow apron speckled with paint). This is the first year in her new studio after an impressively productive and fruitful year. In February 2021 she was granted the Foundation of Contemporary Art’s Helen Frankenthaler Award for Painting (2021). On September 22, 2022, she will be honored, alongside Chicago art-dealer Monique Meloche, at Chicago Artists Coalition, Works in Progress: Radiance and Reunion. Add to the accolades her recent appointment as F.H. Sellers Professor in Painting at the School of the Art Institute and it’s a wonder how she does it all.

“Why did I suddenly move to Michigan?” She says, “I listened to that voice that said ‘Girlfriend, you need to be here.’”

By “here” she means a 2,500 square foot barn-turned-studio with lots of natural light, replete with a library, quotes by Frida Kahlo, Rainier M. Rilke, and John Cage, house plants she brought from Chicago—and paintings of course.

One observation from the move was the change in color-scape, and how it makes a cameo on her canvases in surprising ways: “I’m surrounded by a lot of brown, lately, from all the trees and mud. There’s even a hops farm and a prairie next door. I’ve been living in the city for so long that the move was a huge transition. The chatter you usually hear in the city disappears.” Since listening plays a major part in her practice, she uses the change in volume to muse over the artists she invites onto the canvas. “I spend a lot of time listening to them instead, and searching for patterns.”

*

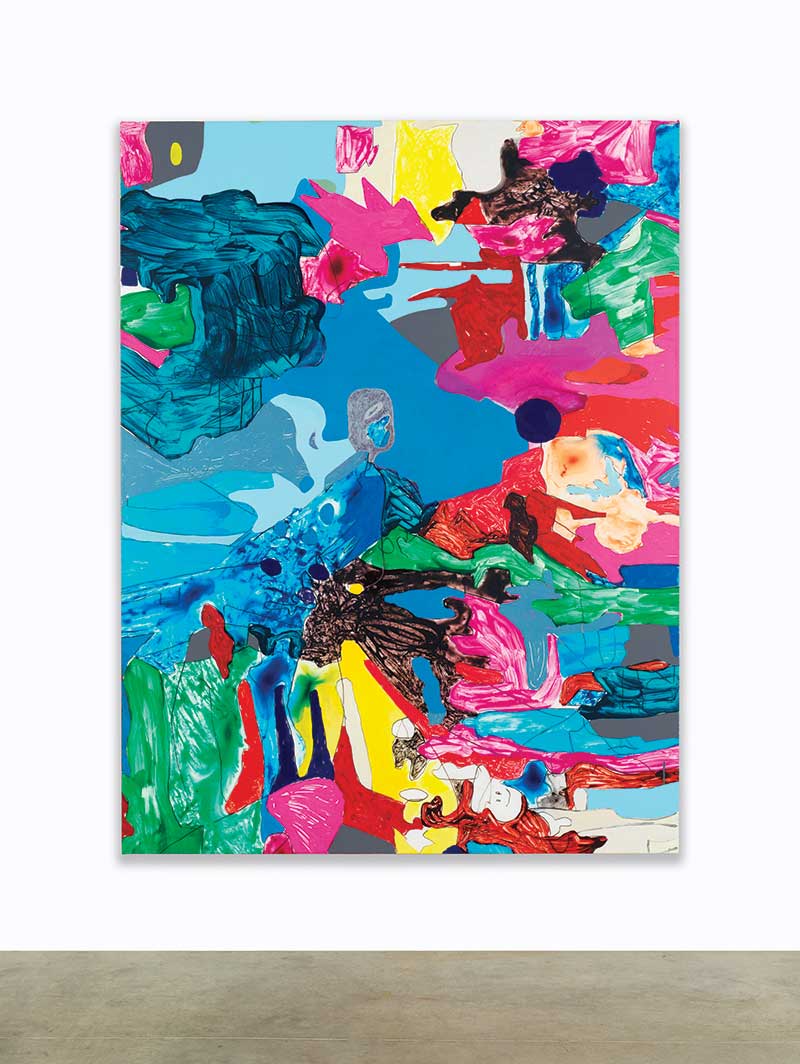

Alvarez is currently working on a new painting, in all its kaleidoscopic glory, for her son. “I just finished putting some bling on it.” Next to it are a couple of paintings from Pica Pica, a series loosely based on Picasso. Several paintings from her Pica Pica series will be on view at Monique Meloche Gallery’s booth at EXPO CHICAGO in April.

“I grew up looking at these dead artists, who seem to follow me around like ghosts,” she tells me. “I started bringing Picasso into the studio because he was someone I have looked at for a long time—everybody knows him. Because it was 2021, I thought ‘Wow. In 1921, Picasso painted Three Musicians.’ I could either love Picasso or hate him. Actually, he makes me itchy. Hence the name of my series, Pica Pica— from me pica (it itches)— because I was getting bit by mosquitoes. But also because I wanted to figure [the painting] out.”

To do so, she uses a range of sources such as personal photographs, drawings, and famous paintings. “I have cultivated a way of working where I can source from the history of painting and weave in what is in front of me in the present,” Alvarez explains. “Lately I’ve been inviting Bob Thompson to the canvas, but I find inspiration in everything: Matisse, Kahlo, Piero della Francesca are just a few of the artists I’ve worked with.”

After she manipulates or distorts her reference she is then able to fully dive into the process. “I might enter a painting with a certain color palette in mind, but it might change in order to achieve that harmony. It’s like alchemy.”

Painting on this scale requires the meticulousness demanded of Paint by Numbers—except that in this case the artist is responsible for both lines and colors. “There’s a membrane that gets pierced. It begins with a drawing that is added to, or taken away from. The drawing is a holding pen for the liquid,” Alvarez reveals. Due to the complexities of each piece–and each one comes with a unique set of challenges–Alvarez tends to focus on one piece at a time.

*

Alvarez compares the end result to a palimpsest: an unearthed, multilayered, vellum-y object harking back to medieval history. Her Palimpsest series emerged from that fascination with transparent layers and traces of what lies beneath the surface. She recently finished showing these “chatty abstractions that mix and remix themselves” in GAVLAK Gallery in LA.

“I wanted to work with a series of ten drawings that I had done two years ago, and bring them together. I looked at words that were ten letters long and came across ‘palimpsest,’ which is a beautiful word all about process. It has multiple histories. Painting is like that for me. I assemble it from a Rolodex of images that I cut and paste, not in a collage-sense, but by shifting shapes by adding and taking away from them. I don’t hold on to an ideal, I just love the process of finding, searching, and witnessing the painting become itself.”

Having worked with a myriad of materials, from vellum for drawings, watercolor pencils and acrylics on gessoed linen, to PVC plastic hung from aluminum frames, she explains that, with each layer she learns how the materials react to each other. She seeks balance between the base material, which sometimes peeks out from under matte, subdued shapes, pops of pigment, undirected lines, or bling of course.

“I used oils in the past, but over time I really loved acrylics. You just needed the paint, the brush, the bucket. I loved that it was fake, that it was plastic. It was not beautiful. But I loved the rawness of the material.”

*

Alvarez always suspected she would become an artist. As a student at Fordham university, she was mesmerized by the oversized portfolio her friend was carrying for drawing classes. “It was settled, I was going to take art classes, too.”

Through the encouragement of some of her professors, such as Jack Whitten, she abandoned her tiny paintings in favor of larger, more robust works. This cemented her decision to return to Yale and later Skowhegan. “I just fell into it and never stopped. I can’t believe I’ve been doing this for a long time.”

One of the most impactful experiences was producing artwork at the then PS1 Residency. “I was affiliated with Museo del Barrio in Upper Manhattan in the ‘70s. It was glorious because it was full of Latinx artists. It was the first time that I encountered real collaboration, in that we could work on something together.” The collaborative spirit finds its way into her teaching as well as her practice.“I have been teaching at the Art Institute for over 25 years, and I find that it brings contemporariness and conversation to the canvas. When you are in collaboration with others, the conversation becomes another way of being present. In the same vein, it helps us be critical.” Otherwise, painting can be a solitary endeavor.

Alvarez moved to Chicago in 1998 to take up a teaching position at SAIC and has since become a community staple. One of her first shows in the city was through Hyde Park Art Center, Mambomountain in 2012. In 2017, she was commissioned by the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) to create paintings to be displayed on Lower Wacker Drive.

However, in a manner of months, she experienced a tremendous set of losses. Before the exhibition Here at the Chicago Cultural Center closed, her father died. Three months later, Hurricane Maria swept across Puerto Rico, leaving her to worry about how to reach her mother and sister.

“I was born in Brooklyn, but my parents were from Puerto Rico. It is an interesting thing, because while we are Americans, they were first and foremost Puerto Ricans. In New York we became ‘Nuyoricans.’ In a way that absence makes the longing deeper, there’s a kind of romanticism about it, a connection to a place even when you aren’t on that land.”

While the hurricane brought these connections to the surface, Alvarez was always invested in the process. So, she wanted to create work that stood on its own. It was during this period that she created Air Paintings, or paintings “with little feet,” as she calls them.

When she set out to create the paintings, she realized she didn’t have to work from scratch. “I was able to use the proofs from the Chicago Cultural Center, and work on top of them. Air also became this material I had to consider. I thought about airplanes and the passage from Puerto Rico to Chicago. The whole idea that a lot of them had to rely on planes to see family.”

For Alvarez that was a turning point. Gathering shapes from that painting, and embracing the flexibility of the material in order to make something that you can almost see-through.

“I love to laugh,” she explains. “You have to keep yourself alive! You can’t take yourself so seriously. I like to be the person who is flexible, who can move at the drop of a hat.”

“For people who trust themselves,” says Alvarez, “who have the courage to be themselves, doubts and risks are all part of the process. You have to be willing to take the risk. There is no manual. Plus, there is a mystery to the kinds of processes that choose us.”

In 2022, Chicago Artists Coalition will honor Candida Alvarez and Monique Meloche during its annual fundraising event in September. Candida’s work will be featured in the Museum of Contemporary Art’s upcoming Forecast Form: Art in the Caribbean Diaspora, 1990s - Today (Nov 19, 2022–Apr 23, 2023). If you are in New York, her work in no existe un mundo poshuracán: Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria will be on view at the Whitney Museum of Art Nov 23, 2022–Apr 2023

More information about Candida Alvarez and her work may be found on her website