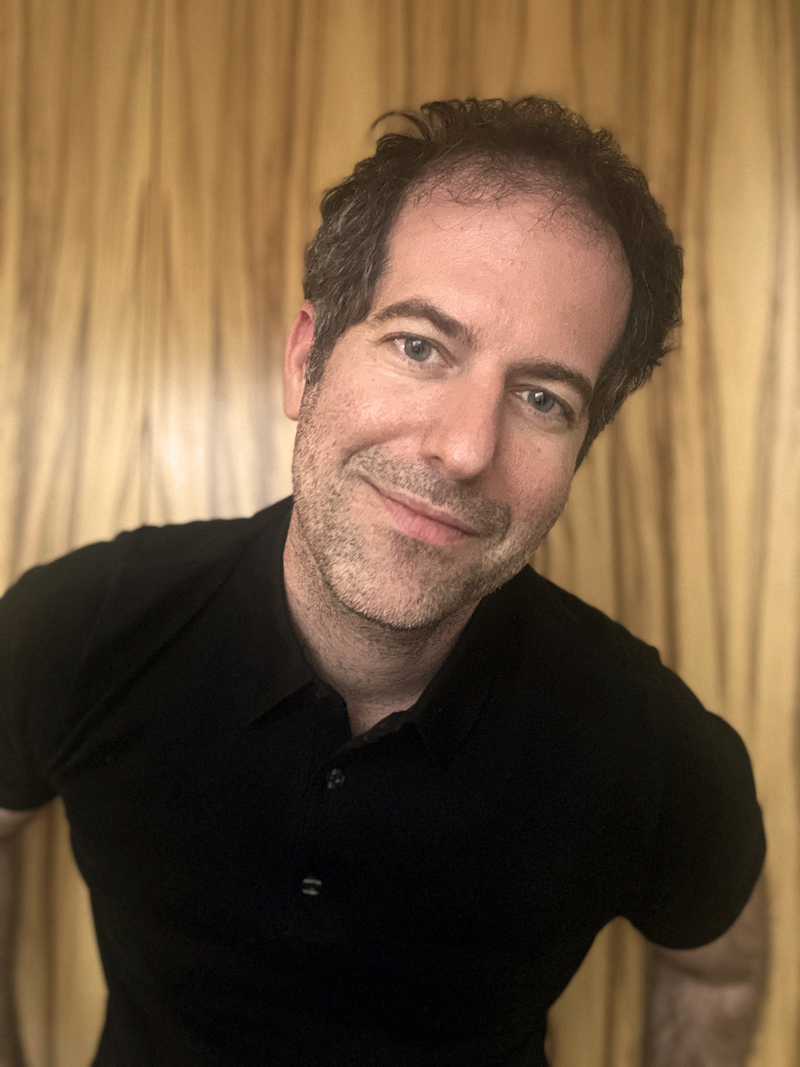

After 50 Years Barbara Kasten Still Finds a New Perspective

By ALISON REILLY

As an accomplished artist with more than 50 years experience, Barbara Kasten is used to traveling back and forth to Europe for her work. But during these past two years, due to the pandemic she stayed close to home in Chicago. Fortunately, she had the space to create a home studio, and when it was safe, she started working again at her Mana Contemporary studio. This fall there are plenty of opportunities to see the fruits of her labor. She has two solo exhibitions opening: the first on September 15 at Sammlung Goetz in Munich and the second on November 4 at DOCUMENT in Chicago.

CGN: Could you tell me about the show at DOCUMENT? I know you are still working on it.

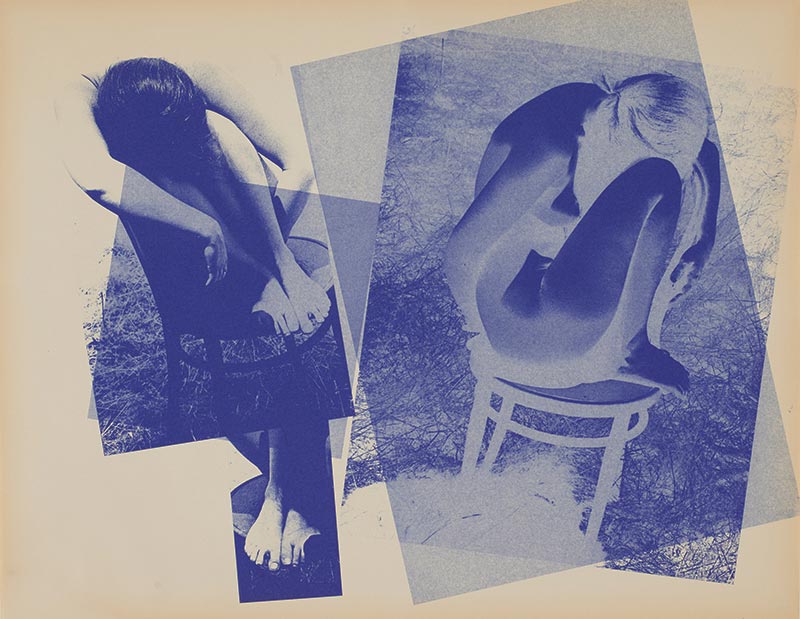

BK: I’m working with Aron [Gent] on a new body of work, and it has to go through a lot of experimental phases to be where I want it to be. I can’t tell you exactly what it’s going to be except there will be unique pieces printed on linen or canvas, I’m not sure which one at the moment. It’s something that I actually entered into photography to do, back in the ‘70s. I really was looking for photography to be a tool in my painting practice. At that time, people weren’t thinking that way, but I started working with photograms

and cyanotypes, because it was still a painting process. Everything I’ve done since has been either a combination of painting, sculpture or some sort of interdisciplinary gesture, because I’m not trained as a photographer, and I don’t think of myself as a photographer. I use photography, but I use it like you’d use a brush or paint. I think that is evident when you look at the 50 years I’ve worked.

CGN: Were you trained as a painter?

BK: Yes, more as a painter. In my graduate days at California College of the Arts (at the time it was California College of Arts and Crafts), I was in textiles and fiber, but I used that as a material to make sculptures– again, not a traditional kind of fiber approach but one where I used the materials of a discipline in an entirely different way than was intended.

CGN: Right. I was looking at some of the photos of the sculptural chairs that you wove. Those are pretty incredible.

BK: I did those when I was on a Fulbright scholarship. That’s an indicator of what I was thinking when I was doing textiles. But then I made some photographs–called diazotypes–they look like cyanotypes but are really a blueprint that architects used. In fact, I did a book on those, when I had my show at the Graham Foundation in 2015. They published all the images I created in a book. We just called it The Diazotypes. It was limited edition, which completely sold out and really surprised me, because now it’s going for like $500, who knew! But it was an important step along the way for me. I never really did anything with figures, this was an abstraction of a figure to go along with the abstract chair.

CGN: With a few exceptions your work has been abstract through and through.

BK: Right. We are creating a book with Skira, an Italian publisher. Stephanie Cristello is the producer/designer/editor of the book. It features only the sculptures and videos that I did from 2015 to 2020. And so that’s in conjunction with the upcoming exhibition at DOCUMENT.

CGN: Some of your works are photographs of installations that you’ve done. When you approach an exhibition, is documentation important to you?

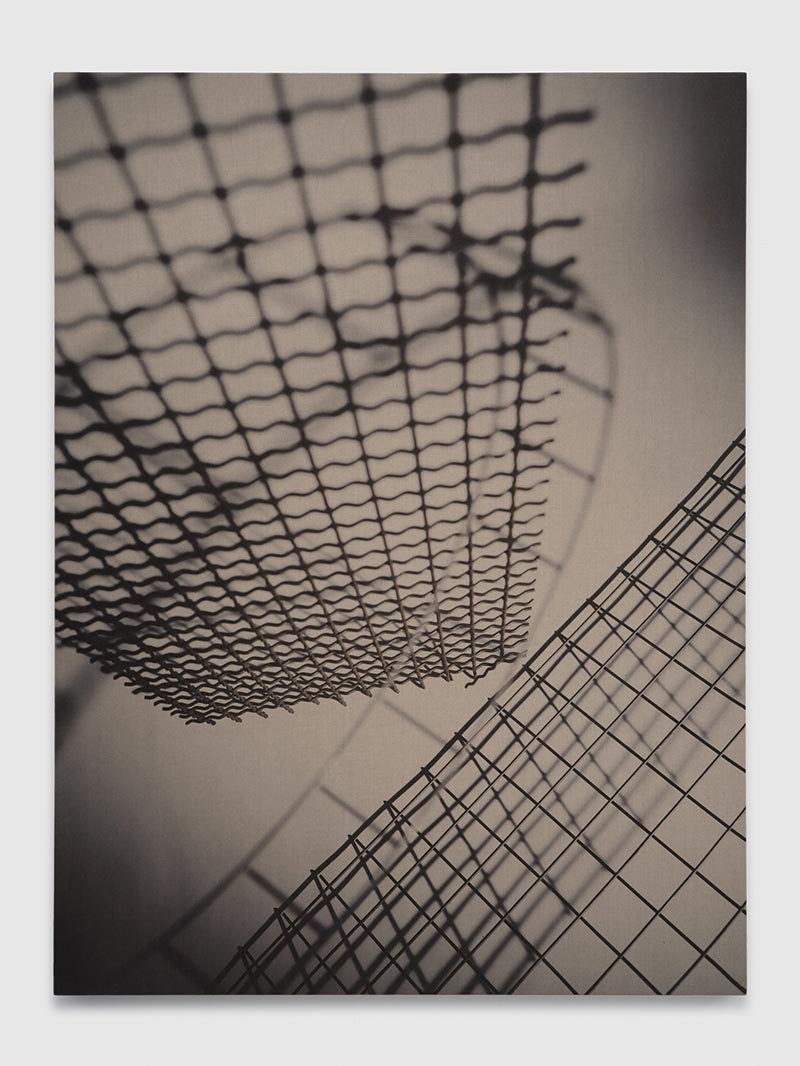

BK: No, maybe that needs to be clarified. I don’t make installations to photograph per se. I work in a three-dimensional, sculptural manner and use that as the subject matter of the photographs. It’s not intended to be a documentation of an installation.

They’re joined together by the interaction of my creating something in space and then stepping out of that role to go behind the camera and record that space on a flat plane. The word “documentation” is true, but it’s not true, which is kind of like my work. Is it real or not real, you know?

CGN: Did you grow up wanting to be an artist? Was it something in your childhood that you thought about?

BK: Yes, I’d say pretty early on. I grew up in Chicago. This is my home town. I went to a Catholic school, and there was a nun who was a painter and within the church she had a great reputation for painting. She wasn’t an art teacher, she just happened to be teaching second grade. She took notice of me, and I started taking art lessons through her tutelage. She instilled this concept in me of being an artist, because I came from a really normal, middle class family, and I didn’t have any dreams based on family history of being an artist.

So she really instilled that. I’d say since second grade I thought of myself as an artist, because she told me I could be.

CGN: You went to a Catholic school in Chicago—was that through elementary school and high school?

BK: Yes, both. I went to a Catholic, at the time, girls school. My dad was a policeman, and he was shot on duty. He was injured, so he went on a medical leave, and then my parents decided to move to Arizona for his health. I was already out of high school, and I said you’re not moving without me, I’m coming! That was my move out of Chicago.

In 1959 I finished at the University of Arizona, and then I went to California for grad school, with a lot of time in between. In 1998 I came back to Chicago at the invitation to teach at Columbia College. I had been in New York for almost 20 years, and I didn’t expect to leave, but the circumstances were that my elderly mother was by herself and my brother was here. Family circumstances and this job offer made it possible. In New York, I was living off the sales of my work.

CGN: How long did you continue teaching?

BK: I taught at Columbia from 1998 to 2010. I was mostly involved in the graduate program there. And of course, my work was different from that of most of the photography faculty and the direction of the program, but that’s what the chair wanted—somebody to work in a different way—so it was actually a very great experience. In fact, I’m still in touch with some students that I taught in my very first year. I just had my 86th birthday, and a couple of students from my first class celebrated with me. I made good friends, and I had a better time teaching than I thought I would.

CGN: I’m interested in how you source the industrial material for your work. I’m also wondering how your access to those materials has changed over the years.

BK: I like going to hardware stores (before they grew into big box stores like Home Depot.) When I was in LA I lived near Venice and the boat industry. I would go poking around in different places to look at the apparatus the [boaters and builders] used–there were pulleys and wires and things like that that they used for the sails and such. I would take those and make some sort of sculpture. Not to replicate anything like a sailboat, or any identifiable thing, but as a material.

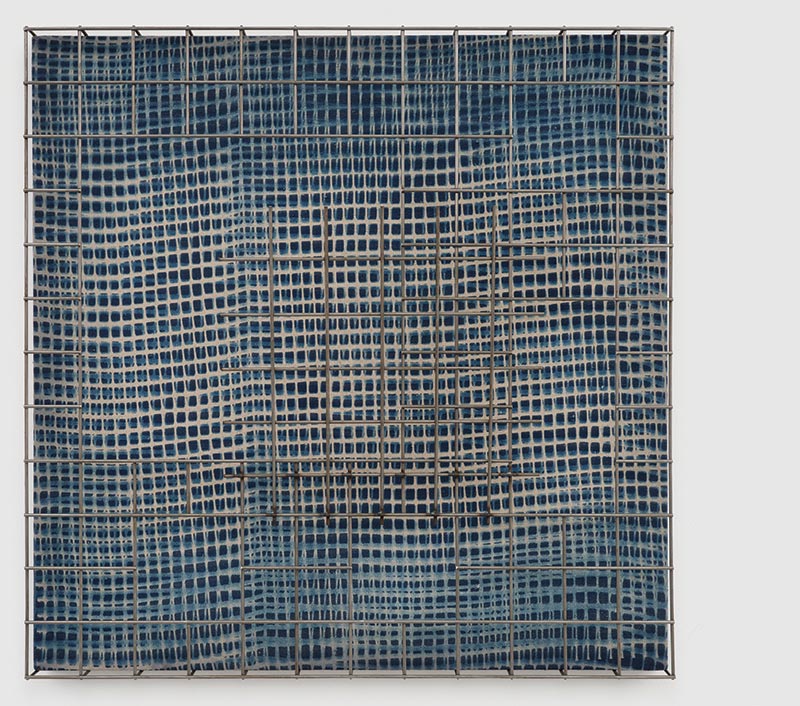

Different materials became really important to me. I did a lot of cyanotypes, and I found a fiberglass screen that was used to keep bugs out of windows, and I used that to create flat forms that then could be manipulated into three-dimensional forms. In using that I began to see all the possibilities when light is used with screen material. I could get different layers of moirés with different lights and shadows. Again, it’s a matter of being curious about materials and hanging out and looking in places where you might find something unique. It was also the time of the light and space movement. There was a lot of plastic around, and people working in resin. I never poured in any resin, but I did use plastic. Once I find the material that has possibilities I really push looking into all it can produce. It’s a curiosity with materials.

Maybe that’s why I don’t do any digital work. I really have to have a hand on whatever it is that I’m creating. It’s not just a visual, it’s definitely my being in the set, my moving and touching and manipulating, it’s more of a sculptural energy than it is a visual one. You can do all these things on the digital screen but it’s a different experience.

CGN: Yes, that’s interesting. I didn’t realize that, but it makes sense given your interests. Could you talk about your relationship with theater and performance? It seems like it’s been important to you to collaborate with performers or bring that aspect into your work.

BK: It was really more inspired by the Bauhaus than it was by any real desire to work as a collaborative effort with performers. That came about because, in the Bauhaus, they accepted so many different disciplines and forms. [Oskar] Schlemmer made wonderful, very bizarre costumes—I love that kind of thing. I was moving in those three-dimensional environments, and it became a static image. I wanted to move away from that into something where motion was added. One step leads to another and so that’s how the video pieces came into play. Just like I used the sculpture in front of the view camera to make an image, I actually incorporate a kind of sculpture in the set of the video. The video is not just a projection on the wall, it actually is an extension of the image into the space. And I incorporate sculptural elements into it.

CGN: At this stage in your career, what are your goals? What are hoping to achieve with your work?

BK: I hope I live long enough to do some more work! I did have a modicum of acknowledgment and reputation back in the eighties in the photo world but it turns out that the ICA Philadelphia show (Barbara Kasten: Stages) and the examination that the curator Alex Klein gave to my work opened up the eyes of a lot of public and curators.

That’s why the book–Barbara Kasten: Architecture & Film (2015–2020)–is interesting to me because I’ve really developed a lot of ideas that I had when I was younger but I didn’t have the opportunity to show. Unless you can put the work out there—if it stays in your head or in your studio, it’s not the same growth. I’m fortunate to be recognized enough to have opportunities and to still be healthy enough to be making art.

CGN: That’s great. And to have that recognition during your lifetime and be able to grow and learn from it.

BK: For me it’s not the recognition as much as the ability to grow. I did a public mural in Toronto right before COVID. Those are things I always wanted to do but that’s an expensive project; you don’t get to do those things unless you can prove that you can or people will take a chance with you. That’s the best part about getting old and still working—lots of opportunities.

#

This interview appears in the Fall 2022 40th anniversary issue of CGN. To subscribe in print click here.