Plastics and Flowers: the Art of Salvador Andrade Arévalo

BY ALISON REILLY

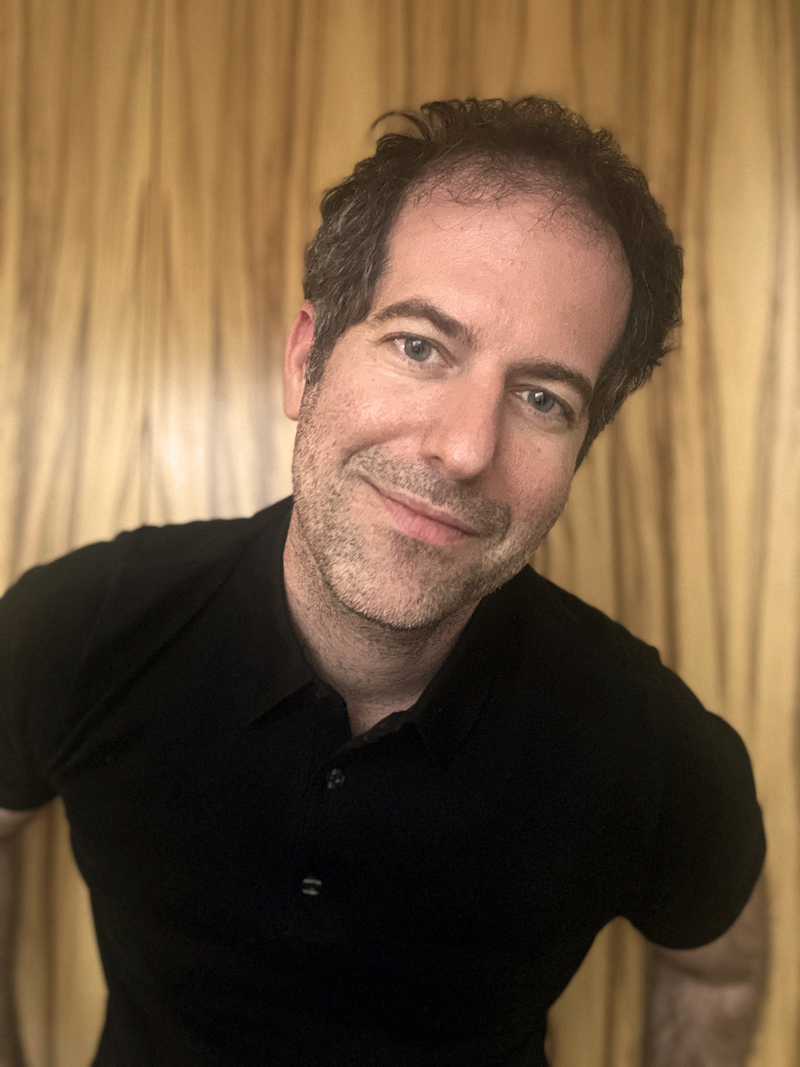

Salvador Andrade Arévalo calls himself a printmaker who paints. Born in a rural area of Jalisco, Mexico, he immigrated to Chicago with his family at a young age. Inspired by his parents and older sister, he took art classes in high school and studied printmaking at Yale University. After graduating from college, he resisted the instability of life as a working artist, and instead worked as an admissions officer for Yale, a staffer on Obama’s reelection campaign, and a Master’s student in Latin American studies at the University of Cambridge. Eventually, he moved to Mexico City and spent five years painting in his living room while working remotely to support himself. Now, after completing his MFA at Yale in 2022, he is back in Chicago and currently a Bolt Resident at Chicago Artists Coalition. His solo show, Olvido, is on display at CAC until April 25, and his work will also be included in CAC’s EXPO Booth.

CGN: What are your earliest memories of making art?

Salvador Andrade Arévalo: Edwidge Danticat, the author, has stated in talks and interviews that all immigrants are artists. In order for immigrants to survive in the US, they must create an entirely new life by pulling from their own internal creativity. They have to have the inspiration, the drive, and the will to survive in a country that isn’t necessarily accommodating to them. For me that spirit, that essence, is an influence in my work. That thriftiness, the frugalness, the need to just make something out of nothing has always been a part of my life, especially as someone that grew up as an immigrant.

My parents didn’t complete high school or college. They only went up to sixth grade. But they’re the most brilliant people I know because they work with their hands. My mom knows how to make clothes. She can look at any knit pattern and she can fashion and replicate it. My dad, before retiring, worked setting up sprinkler systems. for massive corporations, storefronts, and skyscrapers in and around the Chicago-land area. He’s always been crafty. He knows how to use any tool. Growing up in a household with two creative people made me want to work with my hands. In this way, I found art as a logical avenue to pursue in school.

CGN: When did you decide to pursue art formally?

SAA: Well the funny thing is that I don’t think I was necessarily drawn to art classes themselves. I was drawn to the markers and the materials. I was the kid that could color within the lines while everyone else was drawing scribbles. I also grew up with an older sister who was super into art. She studied art in college, and she’s a curator. Naturally it made sense for me to take a lot of art classes, too, without thinking I was going to be a full-time artist later on. I took so many art classes in high school, and I majored in art in college. But it took me five years after I graduated from college to fully decide, okay, I want to pursue art full-time.

CGN: How has your training as a printmaker influenced your current painting practice?

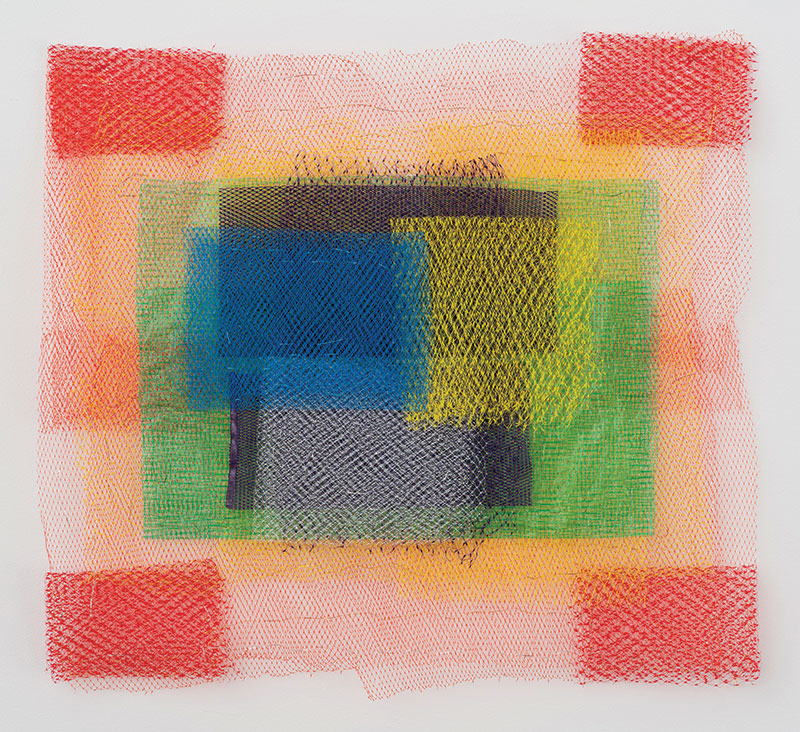

SAA: The way I paint is a transposition of printmaking in the sense that I work with screens of color. In my paintings and my mixed media pieces, I’m always thinking about building up screens of color. That’s what adds dimensionality to my oil painting. A lot of my paintings are very detailed and meticulous, and they seem like I’m using hard edges, rulers, or tapes, but they’re free drawn and painted. This attention to detail comes from my training as a printmaker, in which I had to be very assiduous about everything. And, even though I don’t necessarily print anymore, I still consider printmaking to be a cornerstone of my practice. Having been formed, artistically, with such rigidity allows me to make moves with much more freedom now, because of my technical foundations. It’s much easier to make art with a strong foundation in technique, rather than starting with a baseline of no skills and trial and error.

CGN: Could you talk about the importance of flowers and other motifs in your paintings?

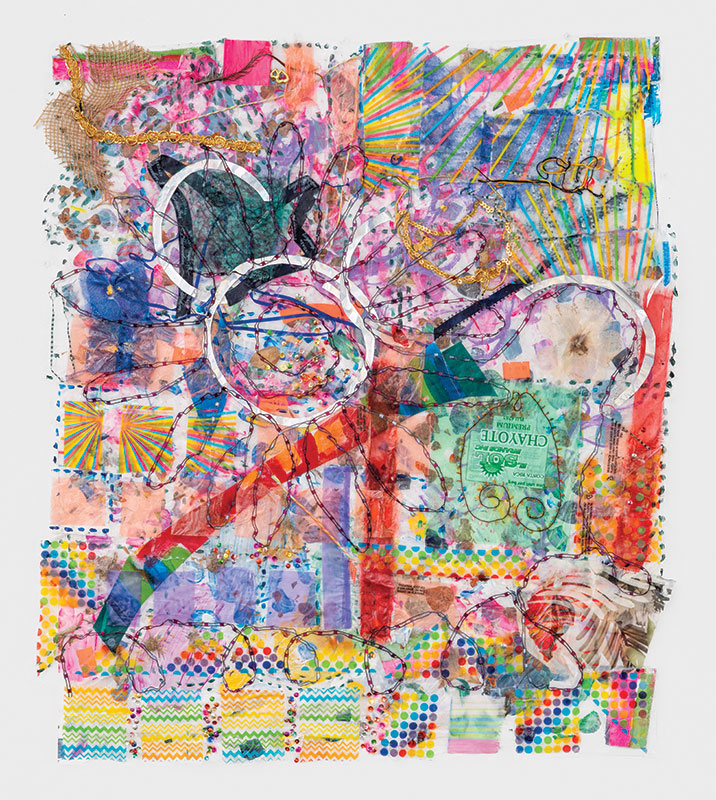

SAA: Whenever I introduce my work right now, I say it’s about plastics and flowers. But there’s a lot of meaning behind both of those things. I’ll start with the flowers. I grew up around gardens. Over the summers when I was in high school, I would set up sprinkler systems with my dad. My family is from a very rural part of Mexico in the state of Jalisco. I was born there. You can imagine a rural place with plants everywhere. I’ve always been in some way, shape, or form, surrounded by plants. I made the connection between farming, warehouses, and my family, and I realized the economic exploitation of plants has kept my family in the labor class.The flowers are also there as a visual trap because they’re so beautiful and seductive. I also depict flowers that I find around Mexico or connect to my Mexican heritage. Some of them may not necessarily originate from Mexico; some were brought to Mexico and became popularized and common in folkloric imagery. Flowering plants themselves have also been so genetically modified that they have their own legacy of exploitation and extraction by human touch to be more attractive.

CGN: And the plastics?

SAA: In conjunction with flowers, I use a lot of single-use, disposable plastics, like food packaging or things used to wrap what you order online. Anything plastic that’s simply thrown away, I use in my work. The first thing you do every day is throw some piece of plastic away. If you think about it, have you ever gone through a day without throwing away a piece of plastic? And the plastics themselves come from petrol, and petrol is fossilized organic material. I’m interested in the concept of extraction and what we consume as Americans in the U.S. is stripped of its origins. The plastic that’s used to tape up an Amazon box, where does that come from? Which country in the global south packed this or made it, and where was it taken from and how cheaply and exploitatively was it removed from its origins?

My family has been migrating between Chicago and Mexico for over 100 years. But always as laborers. This gives you a sense of my family and how these exploitative systems keep people in their same class forever.

CGN: Are you collecting these materials, the food packaging and discarded items, in your everyday life or sourcing them?

SAA: Right now, most of the plastics in my work are from my family’s consumption. I recently completed a piece that was made from collected food stickers. The stickers name almost every country in Latin America. In a way, the piece was a map of the places that grow our food. And since my family in Mexico grows tomatoes, limes, corn, and agave, making this piece was a full circle moment. The food my family members in Mexico grow and sell, could very well be the food that I consume in the US.

So where is our food coming from? Who’s growing it, who’s touching it, who’s packing it, who’s shipping it?

My family members who grow limes have to sell a crate of limes that weights several kilos for pennies. When we buy limes in Chicago, we buy three limes for a dollar. Imagine the markup value of that food source as it passes through the system of wholesale buyers and distributors to the U.S.

“Thriftiness, the frugalness, the need to just make something out of nothing has always been a part of my life.”

- Salvador Andrade Arévalo

CGN: What’s a typical day in your studio like?

SAA: I get up, have coffee, and decide which part of my practice I’m going to devote my time to, especially since I paint by daylight. I’ll set up my oil paints when the sun comes up and then I paint for the entire day. That’s my super concentrated, most intense work mode. But that’s why I also have the other side of my practice, which is more amorphous. The plastic pieces allow me to have more freedom, and not necessarily be strict with a pencil, a brush stroke, or the color choices that I’m making. I bounce between working fast and slow, and I need one to get into the other. The printmaker within me can get so fixated on tiny details. To break myself free from that rigidity, I need the other side of my practice to give me more freedom to play. I never really feel that I complete a piece. I think I can always go back to a piece and have something to fix. I usually just give myself deadlines and say, “Okay, after this day, you see the mistake, but you’re going to have to live with it.”

CGN: Oh no.

SAA: For example, the pieces I’m making for my show at CAC, the March 1st deadline was the hard deadline, and I forced myself to never ever touch those pieces again.

CGN: Would you touch them after the show? Or you let it go at that point?

SAA: No, I tell myself, it’s done. Even though I know in my deepest heart that it’s not done, it’s done. Because I have to stop at a certain point, you know? I get finicky about details. It always goes back to the printmaker within me, who wants everything to be perfectly aligned with no mistakes whatsoever. But a big part of being an artist is moving past

that rigidity and letting the work do what it needs to do. What I think is a mistake might not necessarily be a mistake for the audience.

CGN: What are you exhibiting for your show at CAC?

SAA: I’m including one oil painting and two plastic installations. You know the big potato sacks that grocery stores unpack the food in? I’ve gone to grocery stores, and as people are unpacking them, I ask, “Can I have these?” They look at me like I’m crazy. I’ve selected a ton of them, and I knit them together. It’s a quilt of these food sacks from grocery stores.

Plastics are super light, so I kind of work like a clown car. I can fit an entire installation of just plastic into one normal sized box. They’re so light and airy and flimsy and probably will degrade over time. I can travel with them. I can put up a big installation in a day and take the installation down in the same day.

Then I have a piece that’s a new venture for me. I’m dethreading my old clothes, reversing what a machine can do. I have entirely dethreaded pants and shirts. It’s humorous in the sense that why would I spend hours and hours dethreading my clothes? They do feel very bodily like they had a past life. It also harkens back to the fact that I don’t like to throw things away. The clothes I have ripped or that I no longer use I repurpose in my art now.

CGN: I’m excited to see how those turn out.

SAA: I’m excited about those, too, because I hold onto things. That attachment to disposable things comes from being low income and being raised by family members that didn’t necessarily have a ton of wealth, but they were able to create an entire world, an entire childhood out of the most basic necessities.

I will start a piece and let it sit there for two or three years. Then once I find or stumble across the material that is needed to complete it, I circle back to that piece and I add the missing things that I felt they needed when I first began the piece.

That’s happened with these clothes. I could have donated them, but no one’s really going to want them because they have holes and paint stains. The only other option for these clothes is the dumpster. In the U.S. there isn’t a system to reuse or repurpose things that no longer have a functional use.

But I found the loose strands in my jeans so poetic and beautiful. I just started pulling out the threads. That’s actually how a lot of my practice works. I see something and I touch it and I look at it, and then I’m like wait, it’s doing something that visually is compelling. If I get stuck I will go through my boxes, and I’ll start touching things and looking at them and then seeing what new projects can arise out of the things that I’ve already collected.

This interview is featured in CGN's spring/summer 2024 magazine. To subscribe and receive a copy by mail click here.