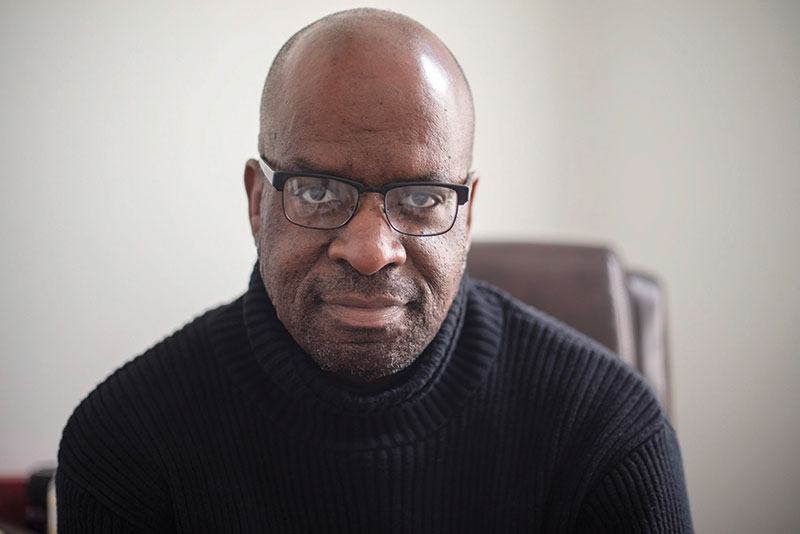

Lee Bey: Illuminating The South Side's Overlooked Beauty

By JACQUELINE LEWIS

Lee Bey is an author, lecturer, photographer, and writer. A South Side native his passion for Chicago stands out in every aspect of his career. Formerly an architecture critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, Bey’s knowledge of Chicago, its culture, and its buildings reveals a deeper understanding of the city for anyone who appreciates the vast array of the city’s experiences.

Most recently, he published Southern Exposure: The Overlooked Architecture of Chicago’s South Side, which captures the South Side through a series of photographs and stories shining light on the beauty and relevance of the area’s architectural footprint and reminds everyone, including Mayor Lori Lightfoot, that Chicago is more than just the North Side and Downtown.

CGN: Can you tell us about your new book Southern Exposure? What drew you to this specific subject matter?

Lee Bey: Southern Exposure is kind of a hybrid. It begins as a memoir and family history of a South Side native and resident. Then it expands into a broader story about the history and architecture of the South Side. Stitching it all together are photographs of South Side architecture and public landscapes. Being a South Sider is what drew me to the subject matter, and my desire as a native son was to tell a different story about the South Side. Too often, the only story we hear is the narrative that the South Side is just a violent ghetto for the rest of the city to avoid. Especially at this moment we’re in now. I wanted my book to say, “Yes, there is that. But there is architectural beauty — some of the best buildings and spaces you’ll see anywhere in this city — that’s been overlooked.” I also wanted the book to make the reader confront the racist housing and lending policies that have robbed black folks on the South Side — and the West Side too — of its wealth and contributed to, if not created, problems we see there.

CGN: What do you think are some of the factors that cause Chicago, and beyond, to overlook the South Side?

LB: In the book, I say outright that it’s race. “Nothing to see here. Just Black people. And it’s unsafe. Besides, anything really important is on the mostly-white north side or downtown.“ That’s been the mindset for 70 years or more. And it’s widespread. I was at a speaking event in Indianapolis last year, and one of the sponsors, when he found out that I lived on the South Side, that I didn’t just write about it, asked me, “Are you afraid to live there?” I said no. But I thought, “Indianapolis is more dangerous per capita than Chicago—what are you talking about?”

Those of us who live on the South Side, we’re not overlooking or not recognizing these well-known architecturally rich places and spaces. We appreciate what’s there. While doing the photography for the book, I’d be out early in the morning or before sunset, and folks would often come out and tell me a little something about the building I was photographing, its official history or even the off-the-books history that was made when the neighborhood became a Black neighborhood. So, we know. It’s others who don’t, especially those who have made architectural, urban planning and preservation policy over the last few generations in Chicago.

CGN: Do you believe that the architecture of an area reveals a deeper story regarding the community it inhabits?

LB: It really does. And too often. That connection makes the story of architecture far more rich. The book talks about the historic architecture of Bronzeville, and they are fine buildings like the former Eighth Regiment Armory, for instance. But when you also understand these buildings marked Black people’s arrival in Chicago during The Great Migration—and these are places where we made history—it adds another dimension to the building’s story, other than cornices, arches, and window openings.

CGN: What photograph from Southern Exposure has the most personal meaning?

LB: That’s a tough one! I’ll have to go with Pride Cleaners at 79th and St. Lawrence. I put Pride in the book because it is a spectacular example of modernist architecture that I bet most people outside the South Side haven’t seen. I’ve loved the building since I was a kid. What makes this personal is while I was writing the book, my cousin McKinley — who was like a little brother to my late father because they were close in age — told me, in the 1960s he and my father would stand in the parking lot of that building and try to figure out how that tilted concrete roof was held up. It’s a story I never knew. The book covers how my father turned me onto architecture, but the fact that he and my cousin were both fascinated by the same zany dry cleaners made me love that building a little bit more.

CGN: Where did you grow up, and how has it shaped your view of Chicago?

LB: I was born on the west edge of South Shore, at 73rd and Kimbark, then we moved to the Avalon Park neighborhood a little further south. It shaped my view in that my introduction to architecture wasn’t the famous downtown buildings or the Gold Coast high rises, but the churches, school buildings, and housing across the South Side. Oak Woods Cemetery is in the book because I saw it as so beautiful and park-like as a kid. That was before they put that thick concrete fence around it that blocks views from the street. Chicago Vocational High School is [in the book] because it’s a magnificent Art Deco building, but it’s also my alma mater.

CGN: Most of your work is Chicago based. What about this city most specifically captures your creative energy?

LB: It’s the contradictions about this city that energize me, frustrate me, and anger me. The city will give you the John Hancock Building, still one of the finest looking skyscrapers in the world, then in the same breath, give you the troubled public housing towers of the old Cabrini Green or Robert Taylor. The city historically holds out opportunities and then keeps them away from black people. Here Martin Luther King was hit in the head with a brick in 1966. And yet this is the same city that raised up Barack Obama, Quincy Jones, Curtis Mayfield, John H. Johnson, and sent Carol Mosley Braun to the U.S. Senate. It elected an openly gay married black woman, Lori Lightfoot, as mayor—judging her solely on the merits of her performance as mayor, not her sexuality. It’ll build a landmark quality building in one generation, then tear it down in the next. That roiling stew of conflict, contradictions, and inequalities is reflected in the city’s built environment. As a photographer and a writer who wants to use architecture as a medium to something about all that, it’s an endless well of inspiration.

CGN: How did you initially get into photography and journalism?

LB: I didn’t develop an interest in photography – other than appreciating a fine photo now and again – until I was about 32 or 33, and I bought a used 35mm Argus C-3 for $25 because I liked its 1950s design. I wanted to take pictures of my young daughters, who were then about 3 and 5. And when my youngest daughter came a couple of years later, I photographed her too. But I was around buildings all day as Sun-Times architecture critic, so I’d shoot buildings, just because I was there. Then I started to like it. And something was born. I got interested in journalism when my high school English teacher, Mr. Doyle, told me I was a good writer. The story is in the book. When he said it, that was transformative. I thought “Yes, journalism. Hell yes.” And the march began.

CGN: Are you currently working on any other projects?

LB: I’m fascinated by the architecture of churches and houses of worship—that comes across a bit in Southern Exposure—so I’m beginning to document more of them. I’m also looking at buildings that didn’t make it into Southern Exposure simply because I ran out of time. In my perfect world, I’d like to do a significantly expanded second edition of the book, doubling the number of images and stories.

CGN: Is there anything else you would like to tell me about yourself or your art?

LB: In the moment we are in with the pandemic and the civil unrest, art and artists become even more important. Sometimes it’s art as a balm – the inclination of ‘Let me go to this museum or gallery or pick up this book because I need to see beauty now.’ Art can also be a way to make sense of our times. To give voice — or provide an alternate voice — to what we are feeling now. And art can also exhort. Mayor Lightfoot hadn’t even taken her oath of office yet when I turned in my last chapter of Southern Exposure to my publisher, but I tell the mayor directly in the book that now is the time for her administration to stand up for the South Side and the West Side. That Chicago can no longer call itself a world-class city if it continues to let these parts of the city just drift.

The mayor and her wife Amy both have of the book. And the mayor also has about a dozen big framed images from Southern Exposure hanging in the reception lobby of her office. So anyone who comes there to meet with her has to face the architecture of South Side. I take all that as a good sign.

You can purchase Southern Exposure: The Overlooked Architecture of Chicago’s South Side through the Northwestern University Press.