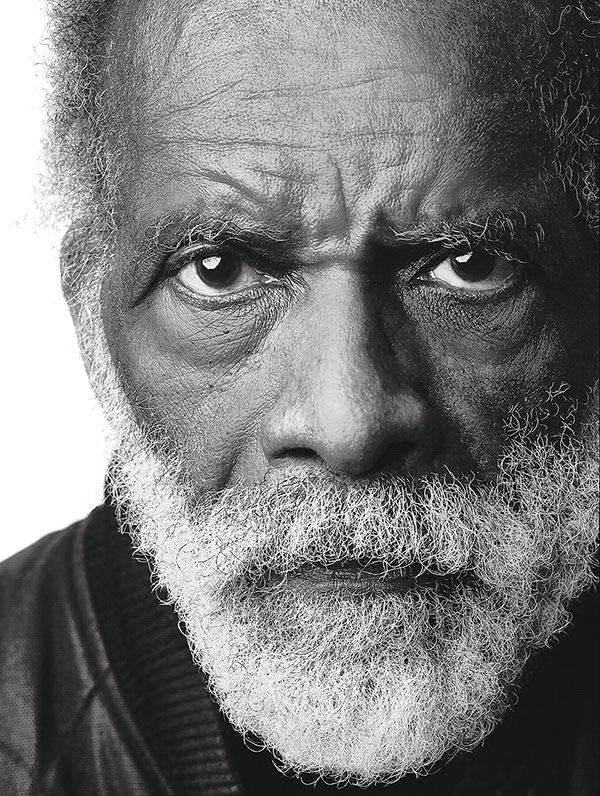

Hard at Work at 87: Richard Hunt

By Anna Dobrowolski

Encountering Richard Hunt’s monolithic sculptures around Chicago is much like running into an old friend, someone you recognize no matter how much time has passed. Hunt’s large-scale public works are out in the elements, soaring into the skyline. Each one signifies you’re in the presence of something distinctly from Chicago, with characteristics that mirror the city’s famed architecture – structures are imposing yet delicately rendered, sturdy but changeable, familiar as well as innovative, raw but refined. The artist’s vision plus hard work is manifested in wrought steel that is put on display to stand the test of time.

Millions of people glimpse Hunt’s sculptures regularly when arriving at and departing from Midway Airport. Additional commissions have been installed on the campuses of the University of Chicago, Divinity School and the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), as well as on the rooftop of the Art Institute of Chicago. Many have become landmarks in their own right. The creator of these magnificent sculptures has been hard at work since 1955. He isn’t slowing down. There is still more to imagine and to make real.

*

Hunt has said about his work, “Public sculpture responds to the dynamics of a community, or of those in it, who have a use for sculpture. It is this aspect of use, of utility, that gives public sculpture its vital and lively place in the public mind.” He has contributed a great deal to Chicago and its legacy of public art. Other cities and towns around the country each bring a little bit of Chicago to their own community when a Hunt sculpture is installed.

When we sat down this winter, inside his Lincoln Park studio that was once a transit power station, the stage was set for an industrial fireside chat about his nearly 70-year career. Warming up beside a space heater – like the ones used for outdoor cafes – in our periphery a massive steel bird manages to materialize from the pages of an open book. Titled “Book Bird,” he explains, the work will join the long list of Hunt’s sculptures in Chicago when it is installed in a courtyard reading space at the Obama Presidential Center, slated to open in 2025. “Book Bird” illuminates how reading and learning allow readers to enter new places and fly free. The work was the first commissioned piece of art for the Obama Center.

Obama Foundation CEO Valerie Jarrett said, “Mr. Hunt’s personal story and creative vision embodies the uplifting experience visitors will find at the Center. Having known Richard most of my life, we are so proud to honor his work here.”

Born and raised in Chicago, Hunt says he was greatly influenced by his mother, an artist and librarian, and he spent much of his childhood enjoying museums and opera performances, fostering his passion for the arts. “I grew up with my parents on the Southside, near Woodlawn and Englewood,” Hunt notes. “When I was around 13 I would go down to the Junior school, as they called it, of the Art Institute on Saturday to take classes.” He was soon captivated by sculpture, even building his own bedroom art studio where he could sculpt with clay long before he discovered wax and soldered wires, and eventually sheet metal and found objects like automative scrap that he could transform into abstract magic.

Hunt went on to pursue an Art Education degree at the Art Institute, and it was here as a student that he began his groundbreaking career. While he undoubtedly found his love for art in Chicago and received his formal education there, the decision to remain in his hometown, despite the pull of the art world nucleus forming in New York in the 1960s, did not come without sacrifices. Hunt reflects, “I investigated the possibilities I had, or ‘should have had’ in New York. Along with friends of mine in art school we asked ourselves, ‘What would we have in New York that we don’t have here?’ I ultimately decided not to move there.” Instead, he was successful taking his works on paper, prints and sculpture to local exhibitions and Chicago galleries. Eventually Hunt says he was interested in gallery representation in New York, and he notes he still travels there, but it’s clear that his life, work and artistic inspiration has thrived in Chicago.

Hunt's work has been exhibited in more than 100 solo shows around the country, and he has received numerous distinctions and accolades, including being the first African-American artist to have a major solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The impressive breadth of Hunt’s work is not just the result of a very long career but also a remarkably prolific work ethic and a seemingly endless well of material. In Hunt’s studio, paging through catalogs of his work I come across a photograph of a young Hunt, climbing a mountain-high pile of scrap metal in Lincoln Park where General Iron’s metal shredding and recycling facilty once was. Hunt’s cavernous studio houses similar maze-like collections of metal, with dead-ends stacked with metallic sheets, inroads leading to maquettes, tools, papers filled with notes. It is both an archive and treasure trove.

Recently, approximately 50 of his monumental works (a dent in his 130 and growing oeuvre) went on view at KANEKO in Omaha, Nebraska. Hunt explains that with such a vast number of works to his name, each piece comes with a unique set of challenges: one needs a larger base, another needs to be sanded smooth, and yet another must be engineered to hang on a wall. Today, at 87, Hunt continues to meet artistic challenges and work on a range of notable commissions, following variable paths to creating art. He tells me that no matter what a certain piece may require individually, a strict timeline to delivery or space to develop organically, each one becomes what it is intended to be. Hunt explains “I tend to have several things in some stage of development, and others that move forward in a chain. Art is something that starts to grow until it reaches maturity. It just becomes what it is.” Much like a career that started with clay sculptures in a bedroom art studio, Hunt has become the artist he was meant to be.

#